In the context of making books (or other reading) a regular feature on my IG, last week I shared and linked to some of my grad syllabi for Family History in Vast Early America including Atlantic and other early modern places. I’ll feature a book every week or so, and aim to say something (brief) about situating that work within family history.

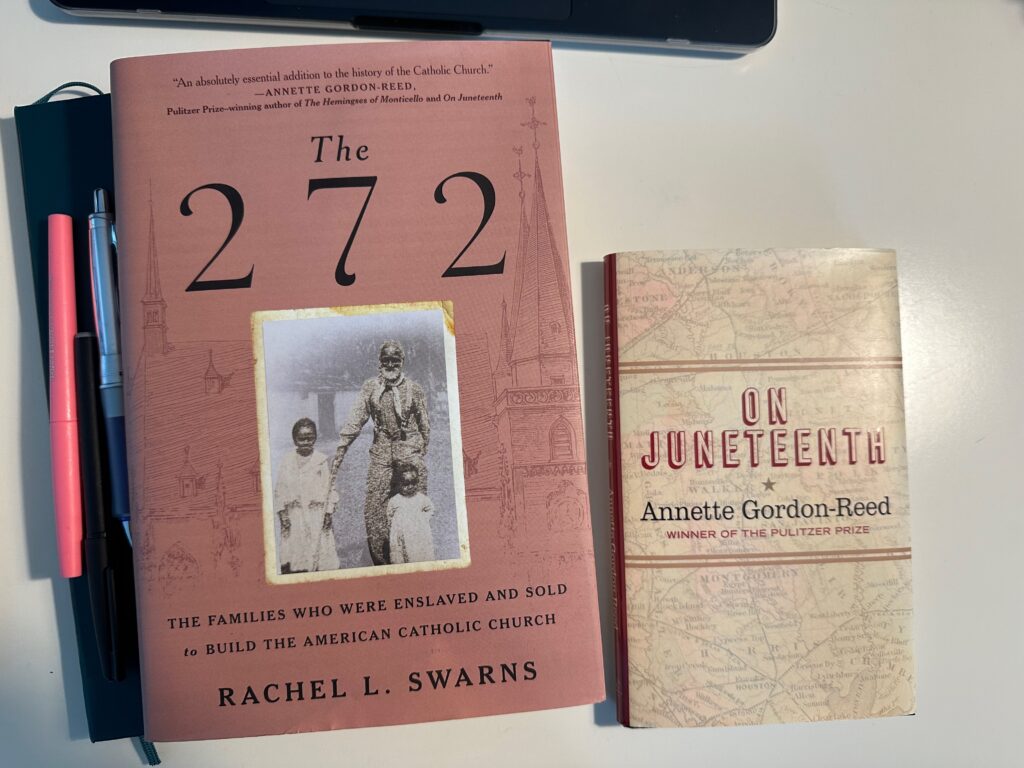

This week I’m featuring Rachel Swarns’s new book, The 272: The Families Who Were Enslaved and Sold to Build the American Catholic Church. The depth, extent, and richness of the historical scholarship on family, intimacy, and kinship among enslaved and free African and African-descended people can’t be even approached here, though I have a post in progress about some important new themes in the literature and hope to share that before long. Suffice to say that one thread, that Swarns is importantly contributing to in this book, is the way that institutions were fully enmeshed in slavery, and enslaved families were connected to many institutional histories.

Swarns follows one of the families to illuminate the history of the Jesuit’s sale of 272 enslaved people in 1838, the profits from which they used to prop up the financially ailing Georgetown University. From the mid-17th century when the Mahoney’s matriarch, Ann Joice, arrived in Maryland and was enslaved rather than, as was promised, indentured, their family experienced dislocation and separations. But they also continued to share their families’ histories. When the 1838 sale ripped apart two sisters, one stayed in Maryland while another was sold to Louisiana. Their Catholic faith remained intact despite repeated betrayal by the Jesuits. At least two women in the family became nuns, working among Black Catholic communities in Maryland.

There are histories of enslaving families here, too. The Carroll family, whose extensive correspondence Ronald Hoffman, Sally Mason, and a team of editors has been working on for years (since Hoffman’s death they have continued to work on the next volumes, to be published by the Maryland Historical Society), reveal among other things the histories of the families they enslaved, appear here as Bishop John Carroll was instrumental in the college’s founding. And as the Jesuits were selling people from place to place in Maryland, he was taking part in something he recognized and understood from his family’s history.

Today the U.S. recognizes Juneteenth (and Rhode Island, where I live, will recognize it as a state holiday as of next year). There is a lot to read about the holiday and its history, but I have read, re-read, and sent copies of Annette Gordon-Reed’s On Juneteenth more times than I can count. But it’s not only because it’s Juneteenth that I recommend the book here, but because it is really tremendous family history by one of its finest practitioners. I keep a small shelf of inspirational work next to my desk, and Gordon-Reed’s The Hemingses of Monticello is on it. It’s a book that looks deeply and with clear eyes at the heart of what many thought of as an American paradox, slavery and freedom (twinned in Edmund Morgan’s title), but that Gordon-Reed shows within the experiences of this family were just essentially American.

Anyway, On Juneteenth is as much her own family’s Texas history as it is history of Texas and the Juneteenth holiday. It’s a wonderfully sized book, spare and compact–but it packs a punch. She says in her coda to the book, in describing why she can write about Texas the way she does, that it has to do with loving the place. If you don’t already know why there is an Annette Gordon-Reed Elementary School in her hometown of Conroe, you’ll want to read about how she de-segregated the schools and about her parents.

“About the difficulties of Texas: Love does not require taking an uncritical stance toward the object of one’s affections. In truth, it often requires the opposite. We can’t be of real service to the hopes we have for places –and people, ourselves included–without a clear-eyed assessment of their (and our) strengths and weaknesses.”

This is true of good family history. We contextualize tough stories, and not necessarily of places we love but sometimes of places we have regard for. Believing that a better, fuller history makes the best foundation for the future is bedrock to my practice as a historian. Swarns is contributing to the history of the Catholic Church but also to the history of universities studying slavery— an ongoing project in no small measure launched by the work of my own now-home institution Brown University and its 2006 Slavery and Justice Report. Georgetown’s research has been led by Adam Rothman and others, and has resulted in robust resources in the Georgetown Slavery Archive. Sharon Leon’s project, “Life and Labor Under Slavery: The Jesuit Plantation Project,” focuses on the enslaved people rather that the Jesuits, and includes a wealth of information about enslaved communities and families. Among universities internationally, the University of Glasgow has been a model, and the University of Cambridge not so much.

Though we can see slavery from many vantages, the economic systems and the institutional histories as emphasized here, these histories are always family histories–families of the enslaved, and the enslavers.