I’m no Austen scholar, and although I’ve been reading Austen for what seems like forever, given the expertise and extraordinary creativity of real Austen fans I’m not sure I’d even count for one of them! But I have certainly read and thought a lot about Jane Austen, the world she created and the world she reflected in her early 19th century novels about provincial England and its place in a world of empires, revolutions, slavery, and war. If you’ve been researching and writing about the histories of genealogy and family history in the long eighteenth century, as I have for a long (!) time, you can’t help but be struck by how these themes are central to Austen. Family, family fortunes (or lack thereof), marriages for love or money or neither, and the vagaries of lineages made and thwarted all figure as prominent concerns as well as crucial plot devices.

Not only because it smacks you in the face with all of this in the first pages but mostly for the spare, assertive way Austen describes her heroine’s fate, Persuasion is by far my favorite of her novels and Anne Elliot my favorite protagonist. It’s close, of course, because who couldn’t be dazzled by Eleanor Dashwood, cheer for Eliza Bennett, or infuriated by Emma Wodehouse? But Anne Elliot is a considered heroine; it’s her analysis of her family situation and her own place in it that makes her such a good guide for the reader. And it begins with the absurd, ridiculous, maddeningly still powerful patriarch, Sir Walter Elliot.

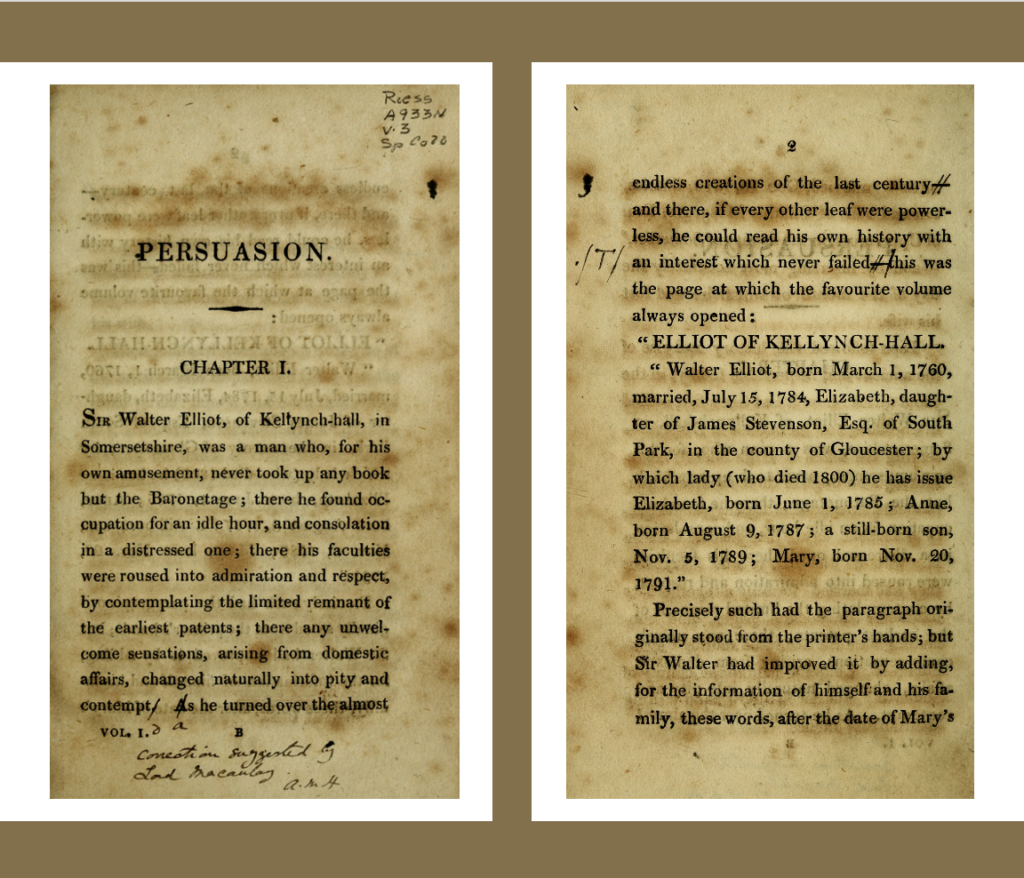

Right from go Austen tells you this novel is about lineage, who cares about it, and what consequences the lineage structure of law and property in England will have for the men and women alike in the Elliot family. And right on page 2 Austen reproduces a (fictional) entry for the Eliots in the “the Baronetage,” from “the page at which the favorite volume always opened.” It describes Sir Walter’s birth, marriage, and children, including “a still-born son” who would, of course, have changed entirely the fortunes of a family of daughters. And “then followed the history and rise of the ancient and respectable family, in the usual terms.”

The Baronetage that Sir Walter is so entranced by was likely meant to echo The English Baronetage first published by Thomas Wotton in 1727 and revised by him and then subsequent authors over the 18th century. Other guides to the peerage more familiar to modern readers came later. Debrett’s originated as The New Peerage in 1769, becoming Debrett’s at the turn of the 19th century. Burke’s debuted with the reign of George IV, in 1826. A cool thing, if you’re invested in the history of family history as method and practice, is that these volumes all advertised themselves as being authoritative because they were based on reliable sources: “collected from authentic manuscripts, records, old wills, our best historians, and other authorities” as the subtitle to Wotton’s volume (and its subsequent editions) put it.

Though the title of Sir Walter’s favorite volume echoes Wotton, the form is more like The Peerage of England produced by Edward Kimber (who also revised the Baronetage after Wotton’s death) in that it began with the present holder of the title rather than the title’s origins. In The Peerage, each category of peer from Dukes on down is first described and then all the individual titles beginning with the current Duke (or Earl etc.). The Baronetage, for example, begins the first volume of the 1771 edition with the baronets created by James I, when that title began to be conferred in earnest as a way to raise funding and resources for the crown (baronets having obligations, of course). Each entry begins with the first known of the family name, locates them in their geography and estate, and ends with the then-present holder of the title. It matters that a baronet is a hereditary title but not a peerage (which entitles the holder to a seat in the House of Lords among other things); as a minor title but nonetheless a title, the baronetage was ramped up in earnest by James I and subsequent monarchs as a means of raising needed funds. A helpful article on Wikipedia lists fictional baronetages, including another from Austen, Sir Thomas Bertram in Mansfield Park, as well as Sir Thomas Hatt of Thomas the Tank Engine fame/ infamy and Sir Anthony Strallan, poor Edith’s almost-husband in Downton Abbey. So while we are meant to think of Sir Walter paging through his own life story, in fact he would have been treated to its context as part of a longer history of creating titles to serve the monarch’s purposes (which was not, historically, how the peerage liked to think of itself).

Sir Walter also did something that was consistent with the ways that individuals and families collectively used text narratives of family history and/ or other volumes where they inscribed family records: he revised and amended the Elliot entry. As Austen describes it:

Precisely such had the paragraph originally stood from the printer’s hands; but Sir Walter had improved it by adding, for the information of himself and his family, these words, after the date of Mary’s birth—“Married, December 16, 1810, Charles, son and heir of Charles Musgrove, Esq. of Uppercross, in the county of Somerset,” and by inserting most accurately the day of the month on which he had lost his wife.

Jane Austen, Persuasion (1818)

At the end of the family history account, which Austen places at the end of the Elliot entry, he intervened again, with “Sir Walter’s handwriting again in this finale:—“

“Heir presumptive, William Walter Elliot, Esq., great grandson of the second Sir Walter.”

Jane Austen, Persuasion (1818)

Austen was hardly alone in these thematic emphases. Lineage concerns were a mainstay of early English novels; it’s hard to find one that doesn’t turn on a marriage or inheritance plot–usually both. In a work that I appreciate for all the ways it tackles the depth and breadth of genealogy, Professor Erin Murphy wrote about Politics and Genealogy in Seventeenth-Century English Literature ((U Delaware Press, 2011). And more recently, Dr. Rita Dashwood has written about Women and Property Ownership in Jane Austen (Peter Lang, 2022). In Birthright (Norton, 2011), the historian Roger Ekirch recovered the history of what likely inspired Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped, a family story so incredible it could only be understood as fiction.

And for those wondering, of course there is an American angle–more than one, in fact. Austen may have stayed close to the England she knew, but America was ever present in those novels in one way or another. In Mansfield Park the spectre of Caribbean slavery is explicit; in other novels the global wars of empire are necessary background. But the context of the Americas lurks in other ways. Edward Kimber, author of the Peerage and the revised Baronetage, spent key early years in North America and wrote about published about it (including a pamphlet about his service with James Oglethorpe in St. Augustine, Florida).

For me, Austen’s use of Sir Walter’s hyper awareness of his lineage serves two purposes for the novel–and for my own thinking about the wider context for genealogy in a British American context. First, that lineage really mattered; it shaped the experiences, expectations, and the lives of the entire Elliot family, Anne chief among them. But was it just lineage and the connection of property to inheritance–or was it the entailed estate, which plays such a role in Austen novels , depriving daughters Eleanor and Marianne (and their younger sister, Margaret) Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility, the Bennetts in Pride and Prejudice and of course Anne Elliot and her sisters in Persuasion of their home and other family property? The entail only existed because of the certainty with which British law, culture, and custom attached property to lineage, so I would argue it was the former first and the latter secondarily though certainly most immediately for these daughters of Austen novel fame. Second, it shows that lineage was also a matter of interest in the other sense of the word; Sir Walter was deeply interested in and even comforted by a recurrence to his life story as related in classic, class-bound narrative of his lineage. We may think of silly Sir Walter with his excess of mirrors and his constant thumbing of the Baronetage as indicative only of a certain English cultural moment, but in fact he was reflecting a much broader, deeper and more persistent investment in lineage that pervaded British American culture. That’s what my book aims to how for 18th century British American practice though alas early 19th century British fiction is just a little too far afield to make it into the manuscript! Thank goodness for a website. Thanks as always for reading.

Update! Two wonderful readers communicated with me (via Mastodon), adding compelling insights and information about the Elliot name and entry in Austen’s Baronetage. Claire Barnes, who studies Elizabeth de Burgh (nope, not Jane A’s but read on), suggested a couple of avenues from her own social media conversations including this interesting 1953 essay about “Jane Austen and the Peerage.” It suggests that Austen not only used real names for her fictional characters, but ones with which she had direct familiarity or knowledge.

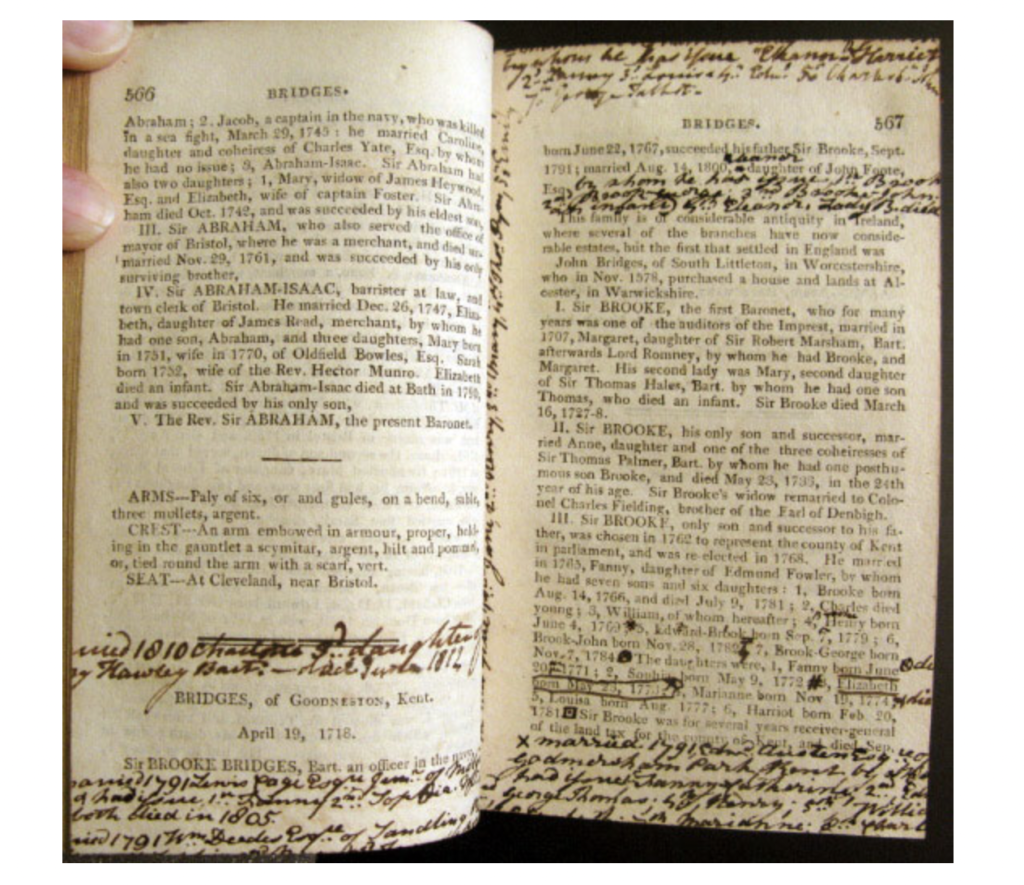

Deidre Lynch flattened me with the link to and an image of the copy of The New Baronetage (1804) owned by the Knights in the library at Godmersham Park– and meaningfully annotated! This comes via a wonderful publication from 2010 on the Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA) website, “Jane Austen’s Reading: the Chawton Years” by Gillian Dow and Katie Halsey. Gosh, was Austen mildly mocking her relations and their interest in the accuracy of their family record among the national august with her description of Sir Walter?

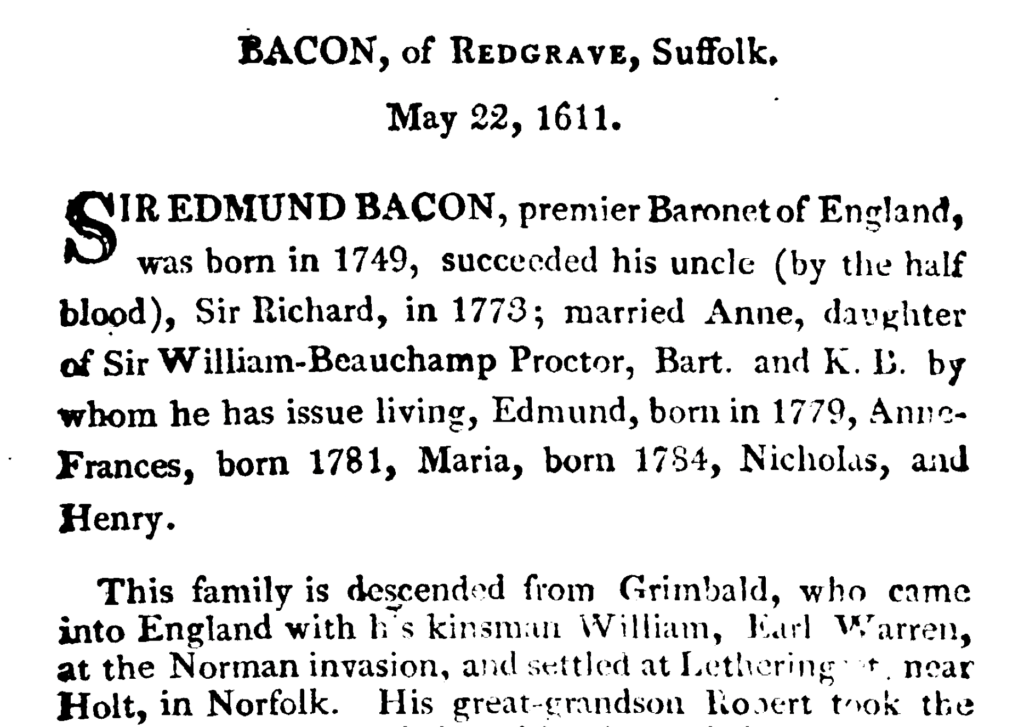

And more to the immediate point, my above comments on the structure of the Baronetage that Sir Walter consulted are wrong; it seems logical that Austen would have been following the pattern of this 2 volume publication instead. A copy of The New Baronetage held at the New York Public Library has been digitized and is available via Google Books. We can see that the format is exactly as Austen describes the Elliots. The example below is for the first of the baronets created by James I and thus always listed first in all of these compendia, the Bacons. The then current holder’s birth, marriage, and children, followed by the family history.

My previous post about social media–learning in community–was happily anticipating just this kind of help. Thank you to Claire and Deidre!