So many posts to write about the history of family history! But a few books and essays I’m really appreciating lately especially in the way they’re coming together around themes of family history as a field that’s really developing in new and important ways, and the exploration of family as a central, explanatory historical experience and phenomenon. The idea that family history explains major historical developments may in fact be backwards; often those “major historical developments” were driven by family imperatives or interests. But that’s for another post. Today is about a collection of scholarship focused on the history of Black families, in slavery and freedom. Each of these holds insights and lessons on family history in toto. And I could add to this group potentially ad infinitum, but for now I want to appreciate what this collection offers and why it seems to me so like a collection.

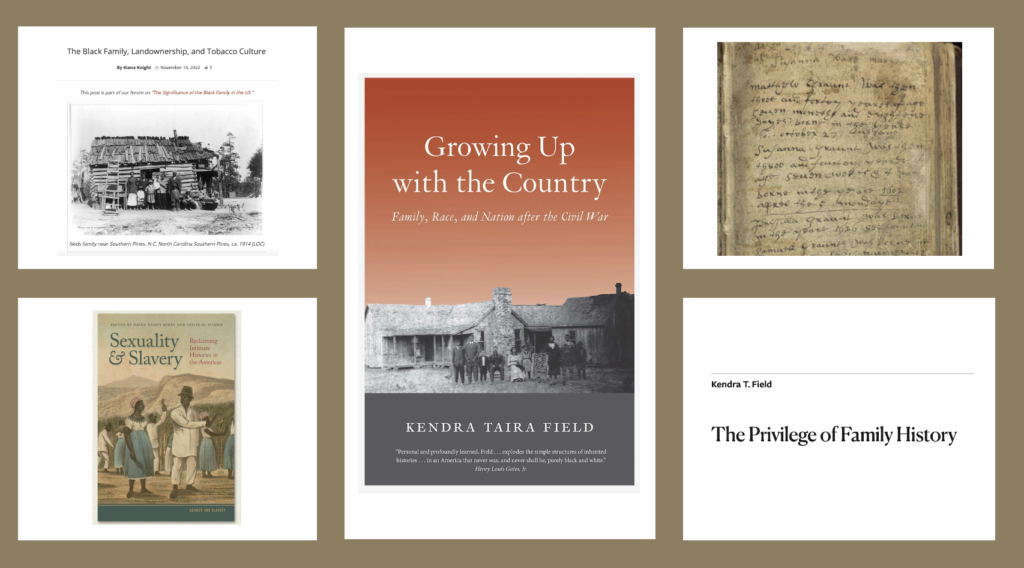

The collection Sexuality and Slavery: Reclaiming Intimate Histories in the Americas (University of Georgia Press, 2018), edited by Diana Ramey Berry and Leslie Harris, is a critical contribution to thinking about family history as history–maybe the history. I read essays in the book–and marked up the Introduction extensively–within months of its publication, but I’ve returned to this book again as I have wrapped up my book on the history of genealogy and begun to work on related projects around sexuality and legitimacy as political terrain. For folks wanting to think about family history as a field, it’s a terrific introduction to why and how sexuality, and particularly its regulation through law, custom, and violence, is such an essential feature. For anyone thinking about the US context for race and gender as key features of family both as an experience and as a subject of cultural and political scrutiny, it’s invaluable.

“The Black Family, Landownership, and Tobacco Culture” by Kiana Knight is part of a forum on the “The Significance of the Black Family in the US” on Black Perspectives, the blog of the African American Intellectual History Society. The history of Black families in the U.S. is deeply connected to the histories of race and of slavery in two ways: first, in the ways that the history of Black families was shaped by racism and by the experiences and legacies of slavery, and then in the ways that Black family histories were told in ways that reflected a deeply racist understanding of the same. The forum tackles both of these alongside analyses and research on specific topics. I highlighted Knight’s essay because she connects the economics of landownership, which reflected how law restricted –and briefly allowed–Black families to build the kind of assets that would make for intergenerational wealth. And she ties this to important rural economies, specifically in the tobacco belt along the Virginia-North Carolina border.

Last year Kendra Field published “The Privilege of Family History” in the American Historical Review (September 2022). This is such an important essay. (If you’re trying to access online outside of a library or university setting, Oxford University Press has some purchase options and/ or you can join the American Historical Association at historians.org.) Field writes about the history of Black family history and also about how and why Black scholars are writing about their own family histories– and what this tells us about the nature of the historical profession, the kinds of sources and methods historians have long privileged, and how we can think about questions of “objectivity” and what those serve/ don’t serve and have facilitated or negated. She writes that:

…by openly engaging their own ancestors, these scholar-descendants have heightened readers’ appreciation of the relationship between scholars and their subject matter….Historians are…increasingly modeling for scholars in other disciplines how best to reconcile the drive for objectivity and relationship to subject matter. Much of the burden dwells in the writing.

Kendra Field, “The PRIVILEGE of Family History”

That point is one of five she concludes with–the others about sources, historical categories, the power of collaborative work, and the duality of the historian-descendant–which are equally important and carefully explored. So much of this is critical for family history as a field– as well as being insightful about Black family history and histories. In short, it’s a really powerful piece, and it gestures too at current and forthcoming work including by Leslie Harris (per above, an editor of Sexuality and Slavery). (Field also quotes in paragraph one Richard White’s Remembering Ahanagran, a book I’ll be featuring shortly.)

But it also expressly draws on Field’s experience in writing Growing up with the Country: Family, Race, and Nation After the Civil War (2019). It’s a book that traces multiple generations of her own family, after emancipation, and shows us the complexity of migration as they moved west, settling Black and Indian towns, and then chose other paths including to Africa. Tina Miles calls it “The most fascinating and cutting edge study to date on black settlers in Indian Territory and Oklahoma during the eras of Reconstruction and westward expansion.” This work is beyond my period of expertise but in addition to appreciating the research and writing, and the reframing of subjects and places especially the American “west,” I’m also attentive to how this complements the mutual histories of Black and Indigenous people and families in the early American eras of settlement, enslavement, and dispossession.

There is so much more to say– and I will, and have in a few other places–about the deeply important history of Black family and Black families in early America. But I’ll leave this here for now, noting how much I’ve appreciated these works of scholarship and the work they are inspiring.