For fans of Deborah Harkness’s All Souls world, 2019 brought two wonderful treats. For those of us in the U.S., we finally got access to the Bad Wolf and Sky productions 2018 adaptation of A Discovery of Witches starring Teresa Palmer, Matthew Goode (and more). And Time’s Convert, Deb’s latest installment of this rich historical-fantasy-romance-and-more, was released in paperback. I’m particularly attached to Time’s Convert because much of it is set in eighteenth-century America, and I am delighted to have it in multiple formats.

One of the things I most admire about Deb as an author is the incredibly evocative historical detail she provides. As an award-winning scholar of science and early modern England, when she describes, for example, the literary and scientific interests of Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke, in Shadow of Night you know there is a deep well of scholarship and source material behind it. Or when she introduces the Voynich manuscript in the Book of Life, of course there is a rich, complex story (and mystery) behind it. In both the “Wider Reading and All Souls Resources” section in The World of All Souls (pp. 479-481) and on Deb’s website where she has posted “Further Readings“ you can read about her own scholarship as well as some additional background.

For Time’s Convert the All Souls world comes back to North America. This was an important setting for multiple strands in the first three novels, including Marcus (later Whitmore) MacNeil’s birthplace in mid-eighteenth century Hadley, Massachusetts, his fateful encounter with Matthew Clairmont at the Battle of Yorktown, and then his violent revelry in early nineteenth-century New Orleans.

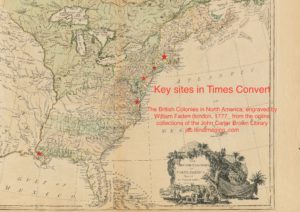

Key North American Sites for TC.

Now we learn much more about these places and events and many others that fill out Marcus’s story, and how it relates to the larger Bishop-de Claremont clan. The story moves from colonial New England and the mid-Atlantic to early national New York and Philadelphia and New Orleans, with some key developments in places such as Boston, Massachusetts, Trenton, New Jersey, and Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

Deb posted a link to the Pinterest board she created while working on the book, and it offers a multi-dimensional bibliography of sorts–wonderful images of evocative places, and period material culture including architecture, clothing, and medical instruments that were essential to building the texture of the book’s setting and background. And, as part of the excitement about the paperback release of Time’s Covert, Deb described for The Week six of her favorite books set in the period of the American Revolution. I love them all! And –yay!– one of them is the diary of Hannah Callendar Sansom that Susan Klepp and I edited, and introduced with substantive chapters about the politics of courtship in Philadelphia, the challenges of motherhood, the power of a woman’s temper– and more.

Of many possibilities, I selected here ten early American places and themes that I found to be especially compelling aspects of the Time’s Convert story, and offer some extra readings and resources I thought fellow fans might enjoy exploring. There are so many wonderful things to read, listen to, visit, and watch about this rich historical period that the below represents only the very tip of the proverbial iceberg. No major spoilers here, but there are some pointers so if you haven’t finished reading the book you’ll want to do that first.

I’ve started with five topics, and will have five more next week in Part Two, so be sure to check back.

❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧

1. Thomas Paine and Common Sense

Of course we have to start with Thomas Paine; Paine is a vital force and Common Sense is a critical theme in the book. Marcus carries that pamphlet (less than 50 pages in its first edition) with him everywhere, and later has it bound. It is a sort of talisman as well as inspiration.

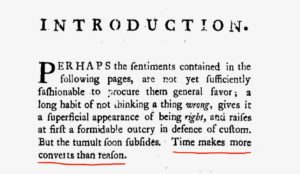

Common Sense was an extraordinary piece of work, and possibly the best-selling work of its time. The quote that opens Time’s Convert, and gives it its title, is in the very first paragraph of Common Sense:

“Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages, are not yet sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favor; a long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason.”

From the first edition of Paine’s Common Sense (Philadelphia, 1776)

The sentiment Paine expresses is pretty pessimistic. People often think things they have known for a long time are acceptable, especially if those things are not immediately challenging their family’s wellbeing. They might be suspicious of new things or ideas, regardless of their relative merits. But he went on this pamphlet to lay out a case against monarchical government that captured both the spirit and the political theory of a democratic moment. There are several excellent online resources for reading Paine’s work, and for reading about Paine.

A digital edition of Common Sense is one of the Paine publications in the Lapidus Collection at the Princeton University library.

You can find a great online project tracking the explosive spread of Common Sense around the world here. I’m especially proud of this project’s co-author, Marie Pellisier, who is now one of my PhD advisees at William & Mary. The Institute for Thomas Paine Studies at Iona College has some great Paine projects and collections, and the nearby Thomas Paine Cottage Museum is where he lived from 1802-06.

The Library of America volume of Thomas Paine: Collected Writings is invaluable; it is edited by Eric Foner, whose book Tom Paine and Revolutionary America places Paine in the context of the era’s social and political developments. Want to know more about Paine’s political vision? Historian Seth Cotlar’s Tom Paine’s America: The Rise and Fall of TransAtlantic Radicalism in the Early Republic offers a view of how Americans viewed the potential for radical governmental reform in the decades after the Constitution was adopted.

2. The Seven Years War

This global conflict shadows Obadiah MacNeil, and thus Marcus and his family. MacNeil was in the Massachusetts militia, and he was at Fort William Henry, an iconic episode of the war, memorialized in James Fenimore Cooper’s 1826 novel, Last of the Mohicans, and then in the 1992 film starring Daniel Day Lewis.

North America was only one theater of this war, which engulfed much of Europe in war between France and England and allies across multiple continents and set much of the late eighteenth century (the American and other revolutions, the course of European colonialism, the Atlantic economy) in motion. The taxation schemes (beginning with the Sugar and Stamp Acts) that the British undertook to pay for the costs of that war, for example, were a primary source of conflict with colonists in North America.

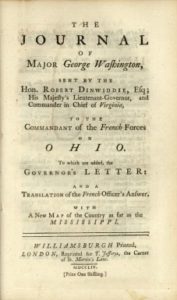

Major George Washington’s Journal (1754)

Daniel Baugh’s The Global Seven Years War, 1754-1763 (2011) is an important single volume on the subject. In 1753, George Washington was a raw 21 year-old Major in the British Virginia regiment. His actions near Pittsburgh formed an essential early chapter in the war, and his journal of his experiences was an 18th-century bestseller.

Fred Anderson is a preeminent scholar of the Seven Years War in North America. His first book, A People’s Army: Massachusetts Soldiers and Society in the Seven Years War (1984) is a foundational study of how colonists and British regular military viewed and fought alongside one another. He looked at letters and diaries to see how their interactions reflected a realization of their differences, and shaped expectations for the Revolutionary conflict to come. Among Anderson’s other books is The War that Made America: A Short History of the Seven Years War, which accompanied a PBS series of the same name (you can still get it on dvd).

Fort William Henry was a British Fort built in 1755 at the southern end of Lake George in what is now upstate New York. This was part of the British defensive efforts against the French. The infamous “massacre” in early August, 1757, has long been the subject of myth and misunderstanding. Archaeologist David Starbuck has recently published a book on the subject, and in this blog post tells a bit about what light the archaeology might –or might not–shed on the subject.

A really key point is that while most history of the Seven Years War focuses on the European powers that instigated warfare, and addresses Native American history in terms of the competing and shifting alliances of various groups with Europeans, for Native Americans the war was yet another that rolled through their lives and territories– in other words, as with all of early American history this war, too, should be understood from the perspective of Native Americans–with Europeans adjacent. For a helpful reorientation I recommend a book I’ve read with graduate students and also read with a local Williamsburg reading group, historian Michael Witgen’s An Infinity of Nations: How the Native World Shaped Early North America.

3. Race and slavey in early New England

Zeb Pruitt of Hadley is an important character in Marcus MacNeil’s youth, and he provides an invaluable insight into the diverse reality of early America. Born into a free black family, Zeb is still, of course, acutely aware of the impact of racial prejudice and the association of race with slavery. He is not only a compelling character in his own right, but illustrates just how deeply slavery was embedded all across early America.

Two excellent recent books address the significance of race and slavery in New England, subjects vital to understanding the colonial history of the region. Erica Dunbar’s Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge, describes Ona Judge’s escape to freedom from her enslavement by George Washington in Virginia and in Pennsylvania, and her subsequent life in New Hampshire. It also depicts the aggressive (failed) tactics Washington employed to try and recover her. Dunbar describes the challenges for free black people in eighteenth-century New England, including the work that Judge and her husband did to support their family. I wrote about using this book for that same local reading group, and included a packet of source materials, here. Wendy Warren’s New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America also traces the early history of slavery in New England, including the enslavement of Native Americans. You can listen to a podcast about Jared Hardesty’s latest book, Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England, as well as podcasts about Dunbar’s and Warren’s books here and here.

For a long time historians (and popular history) equated the history of slavery with the history of the American south; in fact, there were sharp debates about which region was emblematic of American origins on this basis, whether a region associated with slavery (southern) or abolition (northern). Dunbar’s and Warren’s books, and other recent scholarship, underscore that slavery was embedded in society, economy, and politics across early America.

The Royall House museum in Medford (just outside of Boston), the home of the largest slave-owning family in Massachusetts, is doing a lot of work to interpret the lives of people whom the Royalls enslaved. Among those is Belinda Sutton; her remarkable 1780s petitions for pensions owed her from the estate of Isaac Royall (who had freed her in his will) speak so eloquently to her own specific experience but also reflect that of so many others.

4. Inoculation and the Vaccine Science of the 18th century

Inoculation plays a key role in the story, beginning with Marcus’s experience. To be clear, this form of inoculation is not the same as vaccination, both of which confer immunity. The terms are often used interchangeably, but the earlier form is effective though not as safe. The process involved exposing a healthy person to infection, for example by dragging a thread through the pus of a smallpox sore, then embedding that thread underneath the skin. Advocates of the practice included Queen Charlotte, who continued to inoculate her children despite having lost two to the procedure. Only in the later eighteenth century was the process of exposing a person to the much less potent form of the virus, cowpox, demonstrated to be as effective in securing immunity. You can read about the how the English royal family, particularly Queen Charlotte but beginning with Queen Caroline (the wife of George II and grandmother of George III), embraced inoculation in this blog post for the Georgian Papers Programme by researcher Helen Esfandiary. The post also includes links to Queen Charlotte’s writings about inoculation.

“I have the pleasure to acquaint you that my dear Children underwent their Operation with all possible and more than expected for Heroism, I trust that same Providence which has hitherto given me uncommon success in all my undertakings, will not withhold it from me at this time, as I can say with great truth it is not begun without Praying for his assistance as the greatest and best of Medicines I can put my Confidence in.”

Queen Charlotte to royal governess Lady Charlotte Finch, October 1775.

People were willing to risk inoculation, because it was effective when weighed against the dangers of smallpox. An extraordinarily dangerous virus, smallpox ravaged North American populations. This website at Harvard shows death rates from smallpox from the early 18th to the early 20th centuries. Practiced in the English colonies as early as 1722, inoculation was an example of African medical knowledge making its way to sometimes resistant European populations.

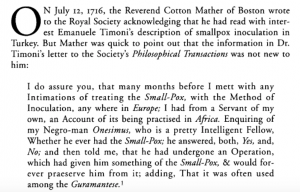

From Margot Minardi, “The Boston Inoculation Controversy of 1721-22: And Incident in the History of Race,” WMQ Jan. 2004.

In an essay in The William and Mary Quarterly historian Margot Minardi explored and explained how information from a man from Africa, not only enslaved but gifted by a congregation to their minister, provided Bostonians with the critical yet contested method for inoculation.

5. Moravians in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

In Time’s Convert the action shifts to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania when the Continental Congress abandoned Philadelphia as the British moved to occupy the city. The scene opens with John Adams (yes, he was there) being taken to task by the Chevalier de Clermont (Matthew). Bethlehem offers readers some insight into the heterodox European religious communities in Pennsylvania, especially the Moravians. One of the singular features of colonial Pennsylvania was its founder, William Penn’s, commitment to religious tolerance. That tolerance could arguably be said to encompass variants of Christianity, but it is worth reading a bit about the history of Mikveh Israel, Philadelphia’s first synagogue, and thinking about the expansive religious practices of “Protestantism” in Pennsylvania. The Moravians (and others, such as the Ephratans) had important communal practices. Kate Carte Engel’s book on Religion and Profit: Moravians in Early America explores what this meant for their economy; you can read an interview with her on the Religion in American History blog here.

One of the most interesting, for me, features of the Moravian community at Bethlehem is the role of single women. I did some research on this for my first book, and Hannah Calendar Sansom discusses some of the friends that she visits in Bethlehem in the 18th century diary Susan Klepp and I edited. Recent scholarship includes this book translating the letters of Mary Penry, a single woman and a Moravian convert.

Historic Moravian Bethlehem has information about how to visit this extraordinary place, and learn more about Moravian religion and culture. For comparison and some important parallels, Historic Ephrata is equally fascinating.

❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧

These are the subjects I plan to cover in Part Two:

6. Economy and Society in British American Port Cities

7. Women’s Education & Literary Culture

8. Benjamin Franklin in Paris (and London, and Philadelphia…)

9. The Yellow Fever epidemic of 1793

10. Early 19th Century New Orleans

❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧

Also, if you’re wondering why “Vast Early America,” you can read more about this idea in other of my blog posts. In short, this is a way of describing the geographically expansive and conceptually rich (vast!) early American past.

Yep, I’m a huge fan of the All Souls books, and a huge fan of their author.

History matters. Historical context is what guides our understanding, and our decisions. That’s what historians are committed to sharing, and that’s what Deb shares so wonderfully, among other things, in her multi-dimensional novels that make us care about the past and the people in it. The past she shows us is really a different place. There are different priorities and values–very different ways of thinking and being in the world, and many of them seem sharply at odds with our own. Yet she also shows us some of the most universal of human experiences, of ecstasy and grief, anger and resolution.

I’ll be back next week with Part Two.

No Comments