The Star Spangled Banner, the garrison flag that was stitched by Baltimore seamstress Mary Pickersgill and flew over Fort McHenry during the War of 1812, is an American icon. As a metaphor, perhaps it is as tired as the stitches that no longer keep the flag whole. Backed by layers of structure supplied by the master conservators at the Smithsonian, the flag now rests at a 10 degree angle, under low light. An online exhibit, “Star Spangled Banner: The Flag that Inspired the National Anthem,” features an interactive exploration of the flag’s origins, its travels before arriving at the Smithsonian in the early twentieth century, and its recent conservation.

What makes this flag so compelling? The combination of its origins, its long history as a family keepsake of the Fort McHenry commander and a precious relic of the young American nation, the anthem it inspired with its “broad stripes and bright stars,” and, as a material object, its history of public display all suggest the warm glow of American nationalism. It pulls with it the colonial revival, the centennial and the bicentennial of the Revolution. It helped to highlight the War of 1812 commemorations. In 2013 the Maryland Historical Society sponsored a recreation of the flag that involved over 2,000 volunteers.

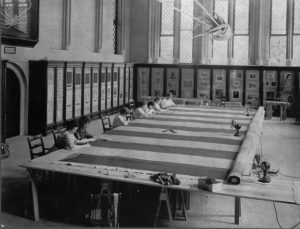

Repair Work on the Star Spangled Banner, 1914. Smithsonian Archives.

What makes it such a powerful metaphor for both the early history and the enduring significance of American national values, however, is the way this tattered flag both embodies and reveals the difficult project of nationalism itself. It survives and is viewed by more than a million people a year because it has been so carefully rebuilt. The conservation strategies and technologies of successive eras have been brought to bear on the challenge of preserving this treasure. Nineteenth-century patching and mending alternated with snipping bits to give as keepsakes. In 1914, a few years after the flag came to the Smithsonian, expert Amelia Fowler supervised ten women who took eight weeks to attach a linen backing (with 1.7 million stitches!) to stabilize it. Decades of monitoring light, heat and dust, in its first fifty years of display at the Arts and Industry building, and then after 1964 when it was moved to a vertically in “Flag Hall” at the National Museum of American History, still left the flag in deteriorating condition. A major effort from 1994-2008 included the creation of a separate, state of the art conservation lab.

In other words, the Star Spangled Banner was private property for a century, and since the early twentieth century has been an increasingly costly public works project. Its endurance was first the result of soldiers at Fort McHenry, but since 1814 has been the work of countless professionals and volunteers. The Star Spangled Banner could not be managed by one family; its endurance has required massive collective action.

But of course there is more to the metaphor than what the flag’s material condition has compelled. Its layers of meaning go beyond the removal of the 1914 linen backing and the application of two new stabilizing layers nearly a century later.

This tattered flag symbolizes, in Francis Scott Key’s telling, Americans’ fortitude in battle. Although only the first stanza of the song is traditionally sung, it has four original stanzas. The second, like the first, queries then extols the flag’s survival. The third stanza turns from the victors to the vanquished.

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore,

That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion

A home and a Country should leave us no more?

Their blood has wash’d out their foul footstep’s pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave,

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Like the flag, the song was cherished in the nineteenth century ( Oliver Wendall Holmes even wrote a fifth stanza for it at the beginning of the Civil War) but became an American national tradition in the early twentieth century. Just a few years after the flag was given to the Smithsonian, President Woodrow Wilson ordered it be played at military and other events, and in 1931 a law was passed recognizing the Star Spangled Banner as the American national anthem.

But what Key was writing about was hardly a straightforward account of a successful battle heralded by the flag’s survival. Key’s history as a slave-owner, his experience with black British soldiers in the months before he observed Fort McHenry under attack, his pro-slavery rhetoric and work as the District Attorney in ante-bellum Washington DC , and the language of the anthem’s third stanza all point to the ways that the flag and the song are deeply embedded in the long history of race and racism in America. In the Washington Post this week Margaret Jordan joined other voices concerned that “Too many Americans still don’t see Black history as their own.” Or, put another way, American historical narratives still too rarely account for the braided nature of national failures and achievements.

The history of the Star Spangled banner reveals other layers, other histories: women’s labor, for example, that made and tended and preserved the flag for centuries. Native American dispossession, which was a dominant outcome of the War of 1812. The point is this: no American history is simple, nor could it be. America at its best is honest about the past, and aspirational for the future. The flag among flags can help us do both.