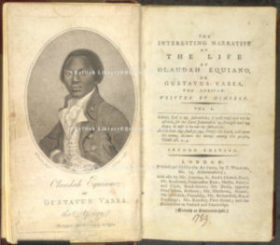

Olaudah Equiano (c.1750-97), or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Portrait. Nigerian autobiographer

I’ve been reading Imogen Roberts’ Crowther and Westerman series of mysteries set in and around 1780s London. In part because of the Omohundro Institute’s work with the Georgian Papers Programme, reading more than my usual intake of eighteenth-century British history has me adding it to my diet however I can. The premise of the novels is the unusual partnership of Harriet Westerman, the wealthy, intellectually restless widow of a naval captain semi-settled on a country estate, and Gabriel Crowther, a gentleman scientist (specifically an “anatomist”). I can recommend the books for the characters and sets (nicely observed furnishings and fabrics). The latest, the fifth in the series,is more gripping and consequential as Roberts takes up, and has Westerman and Crowther contend with, the ways that slavery was both foundational to and yet by a conspiracy of silence largely overlooked in Georgian Britain.

Strong historical fiction is powerful, especially so from my vantage when it swims in the same currents as historical scholarship. I was reading Madison Smartt Bell’s biographical trilogy about Toussaint L’ouverture and the Haitian revolution at the same time as the work of Laurent Dubois and others recovering the histories of Haiti, and after I had started teaching Jennifer Morgan on gender, sexuality, and the reproductive violence of slavery alongside Ralph Trouillot’s Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. I don’t teach the fiction (I know folks who do), but I’m intrigued by how fiction writers are shaped by scholarship, and vice versa.

In reflecting on how she came to this latest topic through the story about Crowther and Westerman, Roberts wrote about how she, too, was confronting slavery’s centrality to early modern and modern Britain. “I thought slavery horrific, of course I did,” she wrote in a blog post, “but I didn’t really think of it as being part of my cultural history, and it is.” The story focuses on the murder of a slave trader turned abolitionist, and the question of whose murderous anger and anxiety was most provoked: the fellow traders he denounced, or formerly enslaved men and women living in London?

Roberts’ historical notes include references to the scholarship of James Walvin, to the Legacies of British Slave-Ownership site at University College London, and especially to the importance of writers such as Quobna Ottobah Cugoano and Olaudah Equiano, citing the editing and biographical work of Vincent Caretta on the latter. (Caretta was one of the OI’s Georgian Papers fellows and wrote in the OI’s blog about his work in the Royal Archives looking for evidence of African writers, including Cugoano, at court.) I’d add a plug for the University of Glasgow site on Runaway Slaves in Britain. The prominence of this and other public attention to Britain’s slaveholding is a critical additional dimension to the expanding and important scholarship on slavery and abolition in Britain. I appreciated the chance to read it through a novelist’s eyes.

No Comments