I find Thanksgiving an especially challenging holiday. In my family it’s always been billed as the holiday we can all agreed on. With a diversity of faith commitments, differing political perspectives, spread across the country, at least we can all agree to spend this one day expressing our gratitude for, especially for the people we love. Right?

Well, no. Or not just. I noted this last year in a short Twitter thread, linking to an op-ed in the New York Times by historian David J. Silverman and then other resources. Thanksgiving’s connection to the 17th century has long recalled a gauzy, stylized 19th century version focused almost exclusively on English settlers. But I’m very aware that when we focus on the least common denominator version of Thanksgiving, eg my own beloved family’s emphasis on gratitude untethered from historical context, or even when we look at the history of its establishment as a holiday in the 19th century, it’s too easy to skip over the critical, consequential and violent 17th century history.

Am I actually arguing that everyone around a Thanksgiving table have a conversation about the 17th century? Of course I am. History is always good for what ails us. And a significant feature of our American ailment has been–not always but often– a disinclination to the hardest and most important history. I will never tire of quoting George W. Bush at the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture: “A great nation does not hide its history.” Many have expressed similar sentiments, many of them doing so more eloquently or with greater subtlety and sophistication, but on that occasion from that president, Bush’s point was and remains important.

I was thinking about all this as I considered why it is that I write an annual July 4th roundup of op-eds and historians’ considerations of the holiday, but I’ve only ever written a Twitter thread for Thanksgiving. For an early Americanist it’s a go-to holiday for reflection on the era. So too is Thanksgiving, with regular, serious reflection from historians and other writers on both the 17th century histories of settler colonialism and then the 19th century histories of national expansion that rewrote the earlier era. (And even a little on the key actors in the 18th century who facilitated that handoff.) The volume seems very different, with so much focus on the anniversary of American independence and its history, though I wonder whether that is changing. Certainly Thanksgiving, like July 4th, offers a key opportunity to consider historical information but also contexts and patterns that have shaped the United States and the culture and society we live in today.

In that spirit, a round-up of some new and recent writing about Thanksgiving:

If you only read one thing let it be this piece that Philip Deloria wrote for the New Yorker last year, “The Invention of Thanksgiving: Massacres, myths, and the making of the great November holiday:”

“Autumn is the season for Native America. There are the cool nights and warm days of Indian summer and the genial query “What’s Indian about this weather?” More wearisome is the annual fight over the legacy of Christopher Columbus—a bold explorer dear to Italian-American communities, but someone who brought to this continent forms of slavery that would devastate indigenous populations for centuries. Football season is in full swing, and the team in the nation’s capital revels each week in a racist performance passed off as “just good fun.” As baseball season closes, one prays that Atlanta (or even semi-evolved Cleveland) will not advance to the World Series. Next up is Halloween, typically featuring “Native American Brave” and “Sexy Indian Princess” costumes. November brings Native American Heritage Month and tracks a smooth countdown to Thanksgiving. In the elementary-school curriculum, the holiday traditionally meant a pageant, with students in construction-paper headdresses and Pilgrim hats reënacting the original celebration. If today’s teachers aim for less pageantry and a slightly more complicated history, many students still complete an American education unsure about the place of Native people in the nation’s past—or in its present. Cap the season off with Thanksgiving, a turkey dinner, and a fable of interracial harmony. Is it any wonder that by the time the holiday arrives a lot of American Indian people are thankful that autumn is nearly over?”

Philip Deloria, “The INvention of Thanksgiving,” The New Yorker, Nov. 18, 2019

In 2017 I did a Twitter thread about some of the first Thanksgiving claims, kicking off with a pretty cranky review I wrote in 2016 about The Pilgrims. My point was that William Bradford would be thrilled to know that his perspective on the Plymouth Settlement via Of Plimoth Plantation was so long-lasting and effectively communicated. I wonder if I’d be more forgiving this year, and am resolved to rewatch.

As historian Heather Richardson wrote in her daily Letters from an American, the holiday should probably be celebrated for its origins in President Abraham Lincoln’s Civil War gesture at national unity in defense of democracy. In 1863 after two brutal years of war, Lincoln called for a national day of thanksgiving– in August. Then in October he called for a second. Only in 1941 did Thanksgiving became a regular, annual holiday. There’s also a piece up on the New York Times that argues that “Thanksgiving is a Celebration of Freedom” because of its 19th century history. I’m not going to wade into why that particular take on the connection between anti-slavery and Thanksgiving seems off, but I’d argue somewhat differently — yes, it’s very important to understand the 19th-century context in which a regional, New England harvest feast became nationalized. But it’s equally important to understand that at the same time New Englanders had been working to erase both their own history of slavery and the continuous history of Native Americans. The New England, including Plymouth and Pilgrims and Thanksgiving, that comes out of the 19th century was the product of a very blinkered view. As ever, the 19th century looms so very large in how we understand early America.

This year for Smithsonian Magazine I talked with Carla Pestana about her new book, The World of Plymouth Plantation. Carla takes on the ways that 17th century writers like Bradford planted the seed of 18th century regional historical enthusiasms that then became a national holiday in the following century. She also writes about the ways that the Plymouth setters were nested in a larger historical context, the first and most important of which was the Native world of the Wampanoag and their neighbors.

There are some very good food-themed pieces this year. In the Washington Post Ramin Ganeshram wrote about Hercules Posey, the chef enslaved by George Washington. Posey ran a complex kitchen creating meals –including a feast for the day of thanksgiving Washington declared in February of 1795–for the family but also for entertaining congressmen, diplomats and other dignitaries. He ran for freedom in the late 1790s, and lived in the free black community in New York until he died around 1812. when Washington was president. A new piece from Neha Vermani on the Shakespeare and Beyond blog of the Folger Shakespeare Library considers “The turkey’s journey from the Atlantic to the early modern Islamic world.” Speaking of turkey, several years ago Yoni Applebaum of The Atlantic wrote a good piece about “How New England’s Turkeys Became City Dwellers.” He traces a longstanding pattern in America of flora and fauna disappearing or adapting is startling ways to the intensity of human consumption and occupation– certainly a pattern early Americanists are familiar with from extensive scholarship. I also liked this piece in the Post about “143 Years of Thanksgiving Coverage.” Journalist Becky Krysta mostly writes about the food, and the politics of the food, but also “nostalgia.” She notes for example that “in 1939, an “early New England Thanksgiving menu” included oyster soup, venison, cornbread and plum pudding with brandy sauce.”

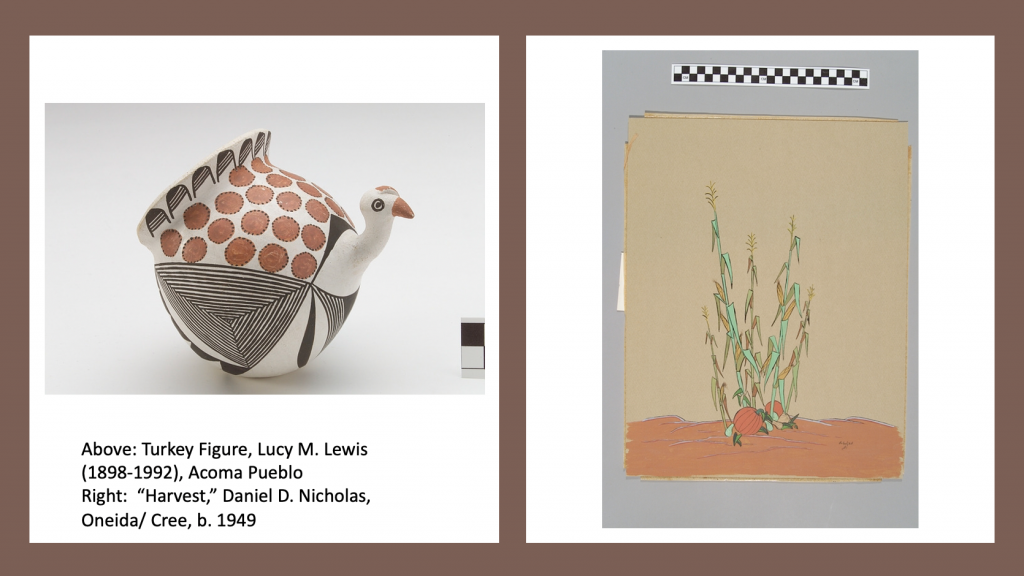

The Smithsonian has a lovely online feature, “Thanksgiving in North America,” with images of objects from around the museums. I really loved these two, both in the collections of the National Museum of the American Indian. There are also some old restaurant Thanksgiving menus, some of them reflecting the food (and historical) nostalgia that the Post article references.

Speaking of teaching, this 2018 NPR story popped up again, focused on teachers working to make Native American history more central to Thanksgiving. A story in the Boston Globe focused on teachers doing less with Pligrim hat construction paper projects, and more with the serious history of settlement. More campuses are committing to land acknowledgements plus revised curricula; this story from Tampa features Anthropologists at the University of South Florida recognizing “the Seminole people, as well as other indigenous groups such as the Calusa and Tocobaga” and in a release “the department asserts that “many of our ideas about the origins of this holiday are historically inaccurate, reproducing damaging portrayals of Native Americans.”

Speaking of historic sites, a key development this year was that Plimoth Plantation changed its name to Plimoth Patuxet, recognizing the two people and cultures that they interpret. They have a good accounting of the Thanksgiving holiday’s development on their site, but more important I think is the FAQ for the Wampanoag homesite interpreters and interpretation. It is well worth taking a moment to read those, and reflect on why they are necessary. Closer to home for me, you can read about early Virginia settler connections with early New England–though this blog post does not mention that men with John Smith were also kidnapping Native Americans in New England. And that Tisquantum, also called Squanto, was taken with intention of being sold into slavery in Spain.

Let me know what I missed. I love reading local news especially, so if you wrote or read something terrific this year, please drop an email or contact me via Twitter and I’ll add it.

I’ll leave you with Alexandra Petri’s commentary on Thanksgiving and American history. “Across the United States, millions of people pointedly spurning CDC advice as they celebrated Thanksgiving during a time of increased covid-19 community spread were excited to hearken back to the very first traditions of European settlement in the Americas . . . . These Thanksgiving reenactors were dedicated to making sure the holiday got the celebration it deserved. “Usually,” another ardent patriot said, “my Thanksgiving celebration is based on a selective and misleading interpretation of history. This year, it will be based on a selective and misleading interpretation of science as well.” Laughing, crying, and hoping you and yours are safe and well.

No Comments