During a discussion about the upcoming 250th anniversary of the United States at a recent conference I referenced my favorite observations about the importance of history to American democracy, from George W. Bush and Annette Gordon-Reed. Maybe you don’t think of these two Texans as a natural pair, but their combined comments really speak to me. In 2016 Bush spoke at the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. It was in the last months of Barack Obama’s presidency, and Bush was invited to speak because he had signed the authorizing legislation in 2003. He said many things on that day that the historic freedom bell was rung to open the museum, but most importantly he said the museum was critically important because “A great nation does not hide its history.”

A great nation does not hide its history. It faces its flaws and corrects them. This museum tells the truth that a country founded on the promise of liberty held millions in chains. That the price of our union was America’s original sin.

George W. Bush, September 24, 2016

Gordon-Reed has written any number of powerful things over the years, but it was a remark at an American Historical Association event with David Blight “Debating and Removing Monuments” that really caught me up short. We’ve simply got to have, she said, “a more mature” relationship with the founders. We need to think about the good and the bad. We need to see the whole of what was, so we can think about the whole of what’s possible.

You have got to tell the whole story about them. It creates…a much more mature attitude about history and historical figures.

Annette Gordon-Reed, July 2, 2020

These two together sum up for me what’s so important about 2026. As New York Times reporter Jenny Schuessler wrote for today, “Across the country, there’s a sense of excitement and cautious optimism, along with no small amount of worry over how to create a unifying commemoration at a moment when fighting about American history seems to be the real national pastime.” Among others, she interviewed John Dichtl of the American Association of State and Local History, which has been working on 2026 for some time, about how to approach this anniversary year in a way that is truly productive and neither head-in-sand celebratory nor grimly exclusive of appreciation and hope.

Earlier this week Jill Lepore wrote, also for the NYT, about her new project on constitutional amendments. She was at Brown last fall and I heard her talk about this project, and she’s spoken and written elsewhere (New Yorker and their podcast among them) about it. With a group of student researchers she’s created a database, the Amendments Project, of all proposed amendments to the U.S Constitution. She’s argued that we need to recover this history, not only of the essentially amendable–by design– nature of the Constitution, but also because it’s become unamendable. Political polarization and the “tyranny of the minority” have brought us to the brink, and one way out would be seize what the founders offered: amendments.

History is an elusive project. Studying history more than a little like studying space: you are always looking to understand what no longer exists. And yet we can make reasoned arguments from the surviving evidence assuming that we are careful enough about assessing that evidence–who produced it and why, what it represents from the universe of potential remnants. The inadequacy of historical methods and analysis are frustrating, but the effort remains vital. We simply can not operate in the present or steer towards a future without a decent understanding of the past.

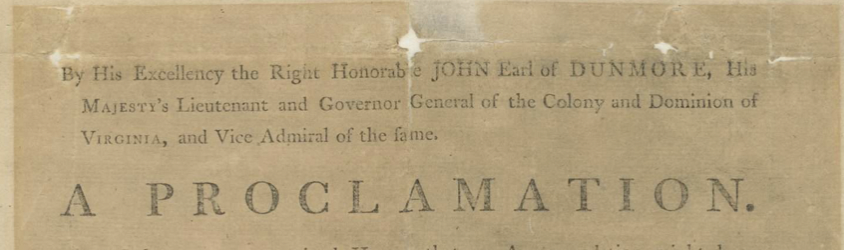

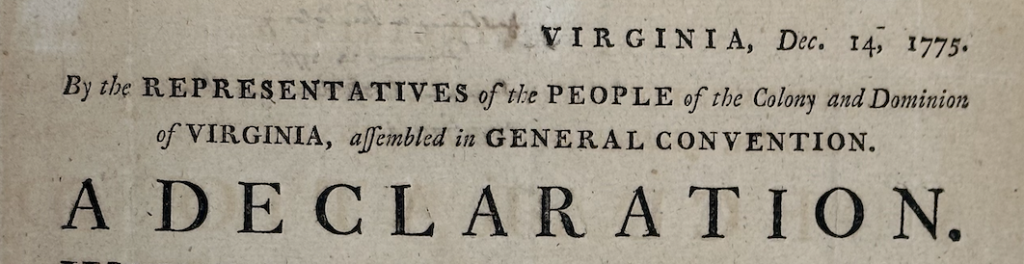

That’s why I included as the featured image for this post the Virginia General Assembly’s response to Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation. In November of 1775 Dunmore famously declared martial law and offered, as the Encyclopedia Virginia puts it succinctly, “freedom to all enslaved people and indentured servants belonging to Patriots willing to fight for the British.” Dunmore’s Proclamation has been the subject of interest and debate among the public and historians, but there is no debating that it instantly made the British a more viable route toward freedom for enslaved Virginians. We know that Black Loyalists answered this call.

And the response of the General Assembly was swift and direct. “All negro or other slaves, conspiring to rebel or make insurrection,” they declared, shall suffer death, and be excluded all benefit of clergy.”

Why highlight this declaration on the day we recognize the Declaration of Independence? The Declaration of Independence is indeed inspiring –if you read it without looking at the full document, when it becomes more complex, more problematic, and more fully representative of our history. Two pieces in The Atlantic, one by Eliot Cohen that encourages us all to actually read the Declaration of Independence and one by Jeff Ostler on the final grievance in the Declaration that articulated a racist and violent posture towards Native Americans, suggest some of this. But you don’t have to come into the second decade of the 21st century to find this combination of appreciation for the potential of its self-evident truths and painful recognition of our nation’s failures to make them manifest for all people: David Walker’s 1829 Appeal and Frederick Douglass’s 1852 What to the Slave is the Fourth of July both nod to this duality.

In short, for me this sober recognition is the most respectful and civic action I can take. And this is how I approach the potential for 2026: as an opportunity to embrace the fullest account of our history as we work towards the future.

In previous years I’ve enjoyed moving through the varied landscape of media to read what’s been written and spoken for the fourth. It’s been my way of taking time to reflect on the meaning of this holiday and of the early American past on which the American nation is built. In the last couple of years I stopped, and this is a modest restart. For now I’ll leave it here.