First, thank you so much to everyone who keeps asking about Lineage: Genealogy and the Power of Connection in Early America! To quote someone currently on a global concert tour, “it’s been a long time coming.” But the book is out of my hands, and I should have a cover to share and a publication date from Oxford University Press very soon. In the meantime, I’ve been catching up on writing assignments, including pieces related to Lineage, and planning for some public audience pieces timed for the book’s publication. I’ve been starting to return to regular posting on my Instagram account, VernacularGenealogy, too.

But I also wanted to turn back to writing about family history as a field, and about some recent work that helps us to see the complexity of families and the choices they made or couldn’t make, in early America. One of the most frustrating things for anyone is when people have misconceptions about an area they know well; I’m sure whatever your field of work or deepest concerns, it’s a challenge when people who don’t have your experience assume something that’s both remarkably and consequentially wrong. Here’s one that my kids’ teachers used to hate: “oh but you only work until 3:30!” (eg when school was out for kids), when in fact they were working exceptionally long hours to plan their classes, grade assignments, and more.

For me, it’s aggravating but also sad when people make assumptions about what families were like in the past based on myth or nostalgia. But it’s more than aggravating because those assumptions can be quite consequential. If you assume that things were always like x until y happened, and x was vastly better, then you would both attack y and argue for a return to x.

Two things in particular are important from my vantage, as a historian of family, and in particular as a historian of family, gender, and politics as entwined historical subjects and experiences. The first is how consistently family is treated as a separate, even individual, historical topic or as a matter of purely private interest. History as a discipline but also as a public pastime tends to focus on Politics, Economy, Military– and the archival materials that are so important to historical work favor those topics, too. Not surprisingly they (histories and archives) tend to leave out almost all women as well as marginalized people. Now, lots of progress has been made here so I don’t want to paint with too broad a brush. But it’s really still a problem that we don’t see families at the heart of history. More of a deep dive about that specific issue in another post.

A second issue, that I’m writing about today, is the idea that families have either mostly looked the same across time or that there was a specific change over time, from big extended families to nuclear families. Most people know, from looking around at their own families, that neither is really the case. We know that law, for example, played a role in keeping some kinds of family structures marginalized or worse– but that’s not the same thing.

There are persistent ideas about such things as “when did women working become the norm?” “Working women” and the relationship between women’s work and family structure is a tenaciously politicized topic. But as historians know, women have always worked. Married women with children have always worked. How we think about what that work was, how it was remunerated, and how it intersected with the labor force at large and with the economy at large is not easy to measure. But every close look shows us the same thing; the historian Judith Bennett, a scholar of the Medieval English economy, for example, has shown both that when women entered specific trades (she focused on brewing), it became less remunerative (this is a version of the pink tax, or the pink-collaring of specific work) and that across time the wage gap between men and women has remained frustratingly constant. She called this “patriarchal equilibrium.”

Recently the Cambridge Group for the Study of Population and Social Structure at Cambridge University released an important longitudinal study of English families since the Elizabethan era to tackle some of these questions by analyzing an extensive set of data. A helpful set of blog posts on “60 Things You Didn’t Know about Family, Marriage, Work, and Death Since the Middle Ages” highlights some of their findings. These include a relatively late age of marriage for both men and women, and relatively small family size. Early America, where my own work focuses, was not the same as England, though there are interesting patterns that were similar among British Settlers in North America. But the diversity of peoples in North America, first and foundationally native people, but also African and African descended people, and a range of different European populations, made for different family forms. Laws restricting marriage, laws prescribing children’s status, including enslaving children of enslaved mothers, and laws restricting property by race and gender all shaped family experience.

Even within some important patterns, though, and the sharp restrictions on many families, families often made different choices or simply looked different because of choices made by their most powerful members. Diversity among families is not a bug, it’s a feature. Step-parents, for example, were a norm in early America. Married couples without any or very few children were plentiful; George and Martha Washington had no children together, and he was a loving and proactive stepfather to the children she had with her first husband. Benjamin Franklin had a son he acknowledged, and then when he married he and Deborah Read Franklin had a single daughter. And these are just the obvious examples. (On Washington’s stepchildren, you should really read Cassandra Good’s book, First Family: George Washington’s Heirs and the Making of America).

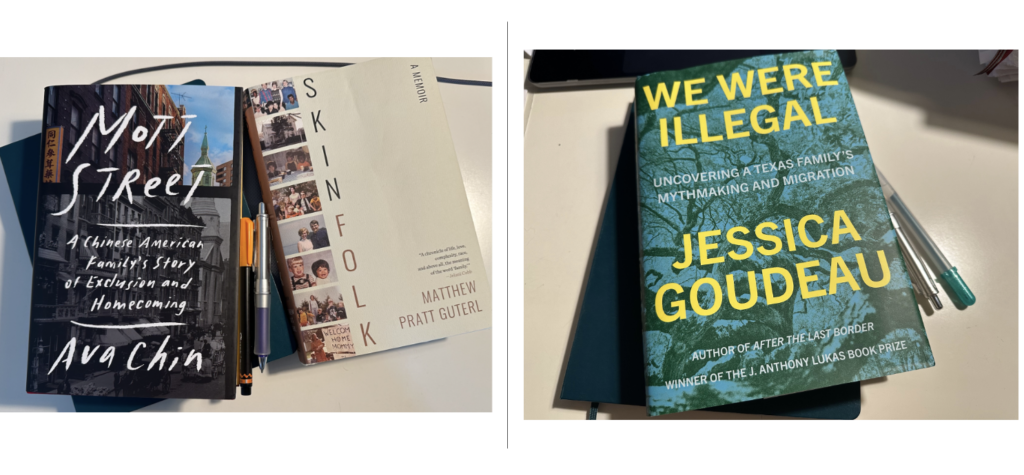

Over the last years I’ve been relishing reading family histories, or family memoirs, many but not all of them written by scholars reflecting on their own families. It’s an accelerating phenomenon and the phenomenal historian Leslie Harris at Northwestern convened a conference about it just this past spring. Among the folks who attended and presented were many whose works I’ve read and appreciated (including Ava Chin– wow, Mott Street is exceptional) and those I am so looking forward to (Martha Jones’s new book, The Trouble of Color and Leslie’s forthcoming one; In this category I also include my Brown U. colleague Matt Guterl’s terrific book Skinfolk). Every one of these books I’ve mentioned is a smart, compassionate, deeply researched exploration of a family and the historical context in which it was shaped, and which it in turn helped shape. Each of the authors, too, reflect on how the extant archival material helps to reveal or conceal the family’s past and how that past as revealed in the archives synchronizes with family memory. I won’t spoil it here but will just say that when Ava writes about her family’s presence in the US archives of Chinese exclusion era immigration, you won’t be able to move until you’ve finished the chapters.

While each of these book shows how the broad patterns of family formation are useful for us to understand historically (no, women didn’t not start “working” in the late 20th century), they also reveal how the particulars of every family are intimately creative adaptations to circumstances– some of those circumstances harsh, even brutal, and sometimes just the regular rhythms of life and the complexity of individual human behavior and decisions.

A book I started reading this week, We Were Illegal: Uncovering A Texas Family’s Mythmaking and Migration by Jessica Goudeau, focuses for the most part on more modern American history, but begins in territory I know much better: 18th century Virginia. As Goudeau notes, paraphrasing a Texan, “Virginia is the mother of Texas.” I really appreciate the structure and premise of the book, in which Goudeau takes a close look at six of her ancestors, each of whom played a role in her family’s transit to and life in Texas. It’s also a book that tries to grapple with the political extremism that gets expressed in Texas towards immigration in particular.

But where Goudeau begins is with the life and fortunes of Sally Reese (1765-1854) of Bedford County, Virginia. And here is where we see yet another example of how remarkably distinctive families could be– and how difficult it can be for us to understand what choices people made and under what constraints. As Goudeau reveals, in 1792 Sally Reese, who came from a family whose fortunes had been declining, had a son with a local man with the distinctive name of Littleberry Leftwich. Littleberry, who may have been called “Berry” and definitely had a host of descendants called that, was from a more prominent and moneyed family. He owned substantial property, and he enslaved at least ten people, including one family of a husband, wife, and their two children. Berry was married, to a woman named Frances, with whom he had six or seven children. But he went on to have nine more children with Sally. And she lived in a house on his property; not the main house, where he lived with Frances, but another on a substantial piece of property (almost 200 acres).

Berry’s situation with Sally might strike us as unusual. But there was more. Berry also had five children with Sally Thornhill. Who also lived on one of Berry’s adjacent properties. And when his wife Frances died, he married again– to another woman named Frances.

The startling repetition in naming notwithstanding, there are other issues here. Plenty of Virginia men had relationship with women who were not their wives; for many of these women these were coerced relationships, conducted in the context of slavery. And these relationships were widely known; plenty of people around Virginia knew about Thomas Jefferson’s relationship with Sally Hemings, and about their children, just as they knew about other like relationships. So people in Bedford County surely knew about the situation at the Leftwich plantation.

There is no evidence that either Sally Reese or Sally Thornhill was enslaved, or that either was Black or mixed race. The evidence is clearer that they were not, that both women were white and free, and that all of their children, while legally bastards (a subject I’ve blogged about and am also writing more about right now), also remained free and unrestrained by either slavery or the servitude that other children of their status experienced.

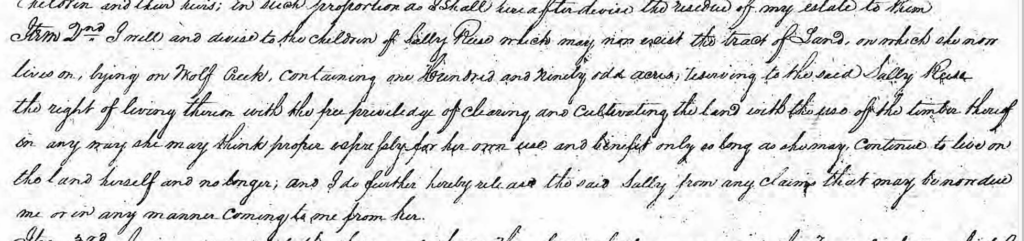

When Littleberry Leftwich died in 1823, he laid out provisions for his full family, or families. All his families. As enumerated in the will, items 1-3 addressed his then second wife, Frances, Sally Reese, and Sally Thornhill respectively. “Item 1st” provided for, after the payment of his debts (standard language) Frances to have the use of 1/4th of his total property, including his house and lands, and the enslaved people–which included those people he described as a family of four–as well as household goods. “Item 2nd” gave to “the children of Sally Reese which may now exist” the property on which she lived. And “Item 3rd” gave to “the children of Sally Thornhill which now exist” a tract that she was living on (interesting described as “part of the tract called Thornhill tract”). He also noted that if either of the Sallys owed him any money, those debts were considered clear.

Goudeau focuses on how Sally’s acquisition of that Virginia property for her children, which they sold and then used to establish themselves in Tennessee, reversed her family’s fortunes. There are obviously lots of questions and implications of Berry’s family arrangements. But among them are that the specifics of any one family can be both understood in terms of the wider contexts and patterns– but also that they reflect individual choices and situations that we may never recover. We can make assumptions about how families did and should look. But anytime we explore family history we are shown just how flawed those assumptions often are.