This is a quick and short post, but I wanted to share a bit about these two books I’d been looking forward to reading: Kate Gibson’s Illegitimacy: Family and Stigma in England, 1660-1834, and Amy Harris’s Being Single in Georgian England: Families, Households, and the Unmarried, both published this year by Oxford University Press.

Both focus on early modern England, which is an important point of comparison for those of us who study early British America. The legal, political, and religious dimensions of family history are structurally similar, though key aspects of these places diverged — European colonies were always different from the imperial center, though the extent of settlement in British America was a divergence from Spanish, French, or Dutch colonies. Two definitive features of colonial British America, the claims to and then dispossession of native lands, and the instantiation of Atlantic slavery, radiated from London as policy but also influences the metropole in myriad ways not least through financial gain but also material culture and ideology (including violent racism).

Both of these books speak to the histories of family and genealogy. And for me, Gibson’s work on illegitimacy is important for the way her research reveals both structural and cultural impacts of illegitimacy. In the context of my own work this plays out differently than the elite folks that she focuses on, but her findings are revealing–and concrete. (If you follow me on Instagram @ VernacularGenealogy you’ll know that I have been tracking sets of bastardy cases across British America as ancillary research to my book).

Gibson recently wrote an interesting piece for The History of Parliament project, “Soft power and stigma: Illegitimate children and the History of Parliament,” which highlights how MPs who were illegitimate either suffered in material ways or felt discrimination. Summarizing her research she noted that “In general, my research revealed that illegitimacy had a significant, measurable impact on an individual’s life chances, particularly boys.” The impact of legitimacy on the structure of inheritance was particularly important: “When it comes to illegitimate men’s influence in Parliament, illegitimate sons of elite families were half as likely as legitimate younger sons to become MPs. This was mainly because they did not inherit landed estates and so couldn’t meet the property qualification”. As important as the material benefits that these illegitimate sons were excluded from or at least benefited from much less substantially, Gibson emphasized the importance of their exclusion or marginalization from the “networks of soft power that ran eighteenth-century society.”

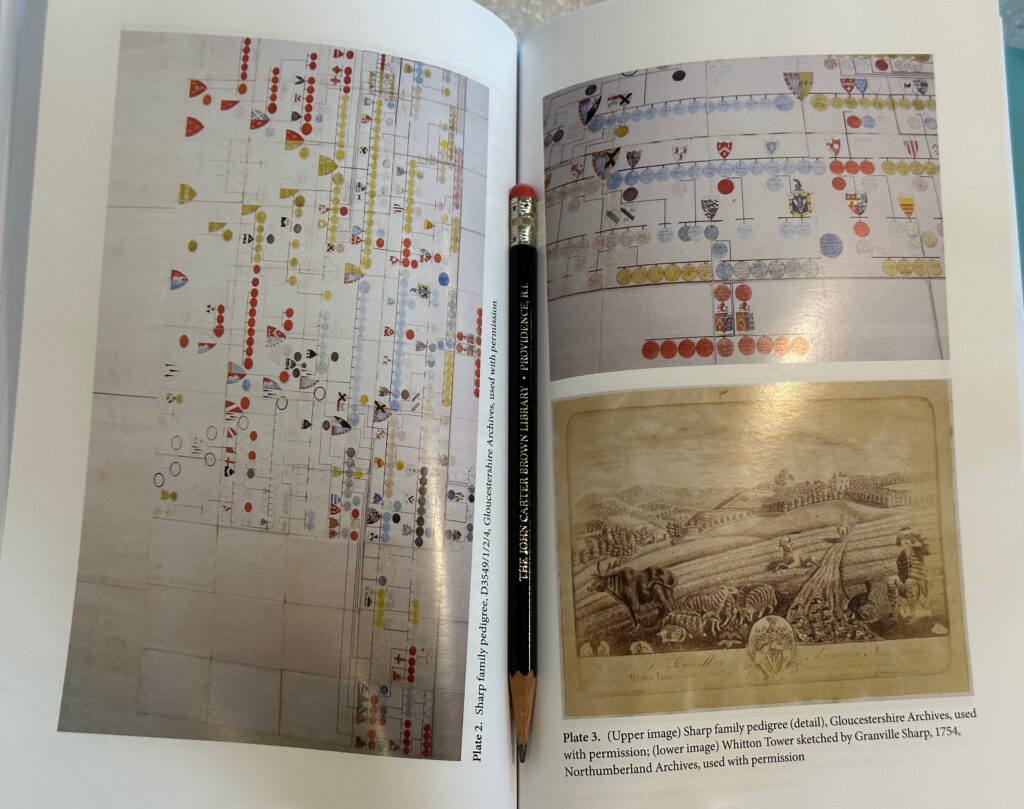

Harris looks at the Sharp family (yes, Granville Sharp the abolitionist but to my mind as importantly his fascinating sisters and other family), and at the ways in which unmarried folks created and extended family relationships– and memory. It’s a close look at an important family archive, which is especially interesting to me. This gorgeous family pedigree created primarily by Elizabeth Sharp Prowse was just one of the family aggregations they left–a family chronicle was the work of many hands. Other familiar items of family legacy (books, textiles, and of course real property) were imbued with family meaning.

There is a deep historiography that each of these books speaks to, and though I’ve just sped through most of the chapters thus far, each is both a good read and a great contribution. I’m looking forward to spending more time with them.