I planned my second effort at teaching Vast Early America as a graduate reading course for Spring 2020. Putting a course together is always an exciting challenge, but teaching this field as a field even more so. Of course I had no idea that the second half of the semester would be consumed by the crisis of COVID-19, or that I would be conducting the seminar from my dining room via Zoom. No one wanted the community we were building in this seminar to depend so quickly on wifi access and videoconferencing. And no matter how resonant with some of thee material and themes of the course, no one wanted this demonstration of how the world is connected through economies, pathogens, and violence or how profoundly inequitable the impacts of the new coronavirus would be. Yet despite–maybe even in some small measure because of –this extraordinary context, the students were remarkably committed to reading and discussion about scholarship.

It was a semester I won’t forget, in part because the pandemic underscored the critical necessity of historical analysis and inquiry but mostly for the students’ determination and care for one another.

The course focused on how to read the vast field of early American scholarship, but also on the key role of archives and archival material in shaping the field. We looked both at the ways that the prominence and relative surfeit of certain kinds of materials long encouraged a particular (largely British American) vantage on early America, but also on why and how a capacious understanding of the era is made possible through new sources and fresh methods of scrutinizing both new and traditional materials. This framing around how archives and scholarship are crucially linked as historical phenomena and as intellectual practices is essential to understanding the history and historiography of (Vast) early America.

The crucial relationship to assess in scholarship –and the one that is vital and portable for transparent and democratic governance–is that of evidence to argument. What evidence supports the contention you are making? This is rarely as simple as “I located a source that reports x, ergo I can assert that x happened.” Footnotes are the historians’ version of receipts; from the notes the reader can follow the evidence and the logic that’s been employed to connect that evidence to the assertions in the text. Understanding the nature of archival evidence, then, is a crucial first step in understanding historical scholarship.

But to understand the nature of archival evidence, we also have to understand something about archives themselves, libraries and special collections or other repositories that collect, catalogue, and make accessible the materials on which scholars rely. For each class meeting we read a collective, core work or two, usually a book or a book and an essay, and then each student also skimmed one of the “also” readings and we discussed those first to set context. On the first day of the course there was an extra dimension. Each student was asked to take a look at an archive or library– a state historical society, or a special collections library–and report on the history of the institution and its collections as well as what kinds of materials for studying Vast Early American the institution held. Was the institution known for its early American materials? What were those materials, and what were the collecting priorities–and the context for setting those priorities–at each institution? This exercise has been illuminating for individual students and for the full class. Their choices were terrific for discussion, too, diverse and compelling. This set us up for thinking about an expansive geography of early America, but also about the nature of the sources we’d be scrutinizing in each week’s reading.

You should investigate, analyze and then write about the origins, collecting emphases, and significance to the early American field of any archive or special collections library you find interesting. As soon as you select one, post the name as we’ll try not to have duplicates. How to find the collecting emphasis of any library? In the about pages, sometimes in highlighted collections. It might not be obvious, but it might be implicit. Any field is in large part created by the archive of materials considered central to its scholarship. In this way, early America as a field has been shaped by a set of holding institutions as much as by scholars/ their scholarship. I don’t want you to necessarily take the position of either traditional or more expansively defined early America in this assignment– just explore. And report back.

the first week’s assignment for the graduate students in the Vast Early America seminar

The archives the students explored were a fantastic array. The Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh (warmed my Pittsburgh heart). The Digital Archaeological Archive of Comparative Slavery (DAACS). The Society of the Cincinnati. The Missouri Historical Society. The Mariner’s Museum. The Early Americas Digital Archive. And more. All fascinating as institutions, and as institutions whose work has shaped the early American field by their collecting, their cataloguing, and their programs. Revisiting these selection months later, I’m reminded of the terrific discussions, and the students insightful observations about the archives they’d taken a look through.

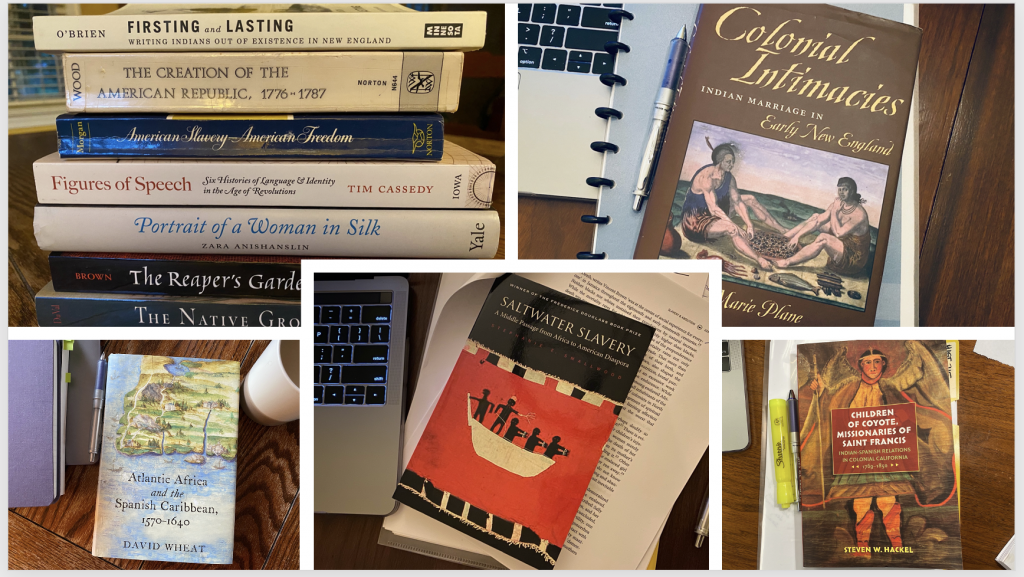

The first and last week readings framed our emphasis on archives, archival sources and methodology. We started with a selection that included a book that is always on my closest book shelf, Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. (You can read about my adventures introducing Trouillot to a general audience reading group here. Short version: it was great.) And our final core reading was Jean M. Obrien’s Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians out of Existence in New England. The readings in between tracked through innovative and classic scholarship. From start to finish, we talked about the evidence that an author used, the method, and the context for each. Those bookend readings then, were essential.

I’ll remember this semester for the pandemic, but also for the startlingly fresh perspectives the students brought to what are still, for me, exciting works of scholarship (whether I’d taught them 2 times or ten). I’m attaching the pre-COVID19 version of the syllabus below, and I wrote about the first Vast Early America seminar, in Spring 2018, here. I’d love to hear how you are learning, reading, teaching, and writing about Vast Early America, too.

The pre-COVID19 syllabus for HIST 715 Vast Early America (SP2020):

No Comments