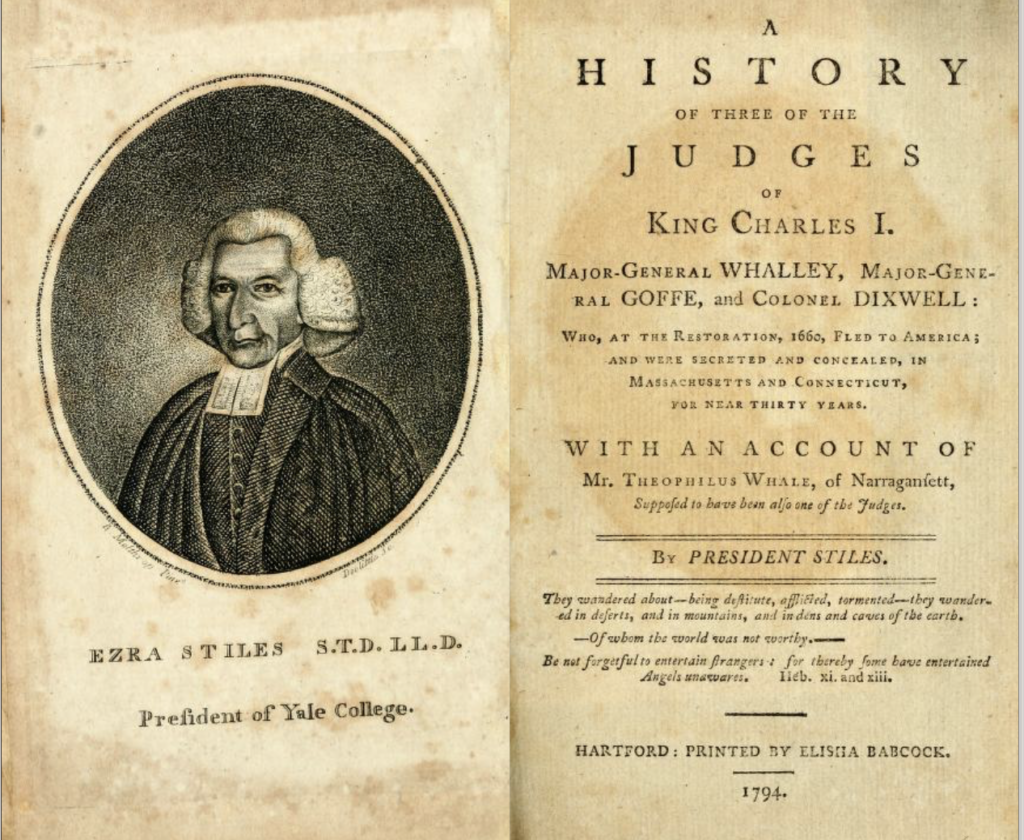

I mentioned on Instagram (@VernacularGenealogy) last November that I’d had a chance to take a quick look again at some of the Ezra Stiles papers that I’d looked at years ago. Stiles was many things– a minister, a president of Yale, a founder of Brown University–but he was also an avid genealogist and local historian. His papers are rich with the evidence of both, and he’s a great example of what I call in my book a “chronicler.”

I was reminded recently of one of Stiles’s publications, his 1794 A History of the Three Judges of King Charles I. I’d been reading historical fiction, as I often do, and had just finished Robert Harris’s fictionalized account of three of the men who had participated in the execution of Charles I in 1649–the regicides– who fled England and lived in New England for decades. (I’ve written elsewhere about how important it is, in my view, for historical fiction to credit and engage with the scholarship that informs the work; suffice to say that in this as in his other books I’ve read, Harris does both.) It led me to poke around a little, including in an 1860 piece in The Atlantic about the New England regicides, and this terrific story (and a book) about an unknown family history by a descendant of one of the last regicides revealed to be in New England. There is also a recent scholarly account of the regicides in New England and the folklore that grew up around their lives on the run. There is much to say about the complex history of the English Civil War, the execution of the king and the restoration a little more than a decade later. Its influence on British America persisted well into the period of the American Revolution. Stiles, for example, dedicated research and writing to this history more than a century –and another kind of revolution–later.

But what had arrested my attention was the Stiles connection, and the attention he lavished on this history. Among the illustrations in Stiles’s book are images of the reputed gravestones of the two most notorious of the New England regicides, Edward Whalley and William Goffe, father and son-in-law. Their graves had long been reported as unmarked, but there have also been centuries of memorials in places including the town green near the Congregational Church in New Haven, and in what was likely their final residence in Hadley, Massachusetts. Stiles was bent on investigating via oral histories, family archives, and town records what might have become of the regicides. It’s a remarkable book, indicative of his practice of collecting and sharing family and local histories.