A couple of months ago, I wrote a post for The Scholarly Kitchen about different types of projects working to engage public audiences with scholarship (especially history). In that post, I related my enthusiasm for a local book group, the Early American Reading Series (yes, EARS), that I lead at the Omohundro Institute. I described how we had read a challenging and incredibly important book at the end of last spring, Michel-Ralph Trouillot’s Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, which generated an incredibly good discussion about history, politics, and power.

A couple of months ago, I wrote a post for The Scholarly Kitchen about different types of projects working to engage public audiences with scholarship (especially history). In that post, I related my enthusiasm for a local book group, the Early American Reading Series (yes, EARS), that I lead at the Omohundro Institute. I described how we had read a challenging and incredibly important book at the end of last spring, Michel-Ralph Trouillot’s Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, which generated an incredibly good discussion about history, politics, and power.

In various posts on this website, I’ve written in a bit more detail about the reading group, starting last fall when I described developing source packets for each meeting. The basic idea is to include primary sources that expose the evidentiary infrastructure of historical scholarship that can help guide the discussion of the book, and that offer a way for readers to extend their experience of the book. I started the packets when we read Erica Dunbar’s book Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge. (You can read about the EARS group book lists and schedule here; and the source packet for Dunbar here; one for Jane Kamensky’s A Revolution in Color: The World of John Singleton Copley here; the one for Trouillot here).

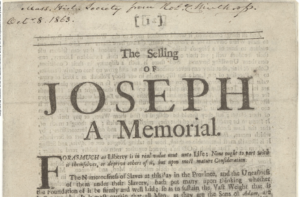

This week we discussed Wendy Warren’s New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America. The source packet was not as full for this book in large part because most of Warren’s sources are not available online; she worked through extensive New England court records. This was a point of useful discussion. Whereas with Dunbar’s book, we could read Ona Judge’s words in an interview she gave to a newspaper (thanks to databases of early American newspapers) and the exchanges between George Washington and his agents as he was trying to chase her down and take her back into slavery at Mount Vernon (thanks to the Papers of George Washington and the really phenomenal Founders Online). It includes for the first time a précis and a link to Nancy Shoemaker’s review of Margaret Newall’s Brethren By Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery, because I wanted us to talk about the significance of Warren’s discussion of Native American enslavement in New England. And I was able to include one key document, a centerpiece of Warren’s final chapter, Samuel Sewall’s 1700 pamphlet “The Selling of Joseph,” because the Massachusetts Historical Society has wonderful online access to the full item (and in high resolution). I also added an example, also from the MHS, of a deposition concerning the contested claims to own two men in Boston in 1740, because I wanted to discuss the ways that slavery appeared in New England court records even if we couldn’t look at precisely the cases Warren was discussing.

This week we discussed Wendy Warren’s New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America. The source packet was not as full for this book in large part because most of Warren’s sources are not available online; she worked through extensive New England court records. This was a point of useful discussion. Whereas with Dunbar’s book, we could read Ona Judge’s words in an interview she gave to a newspaper (thanks to databases of early American newspapers) and the exchanges between George Washington and his agents as he was trying to chase her down and take her back into slavery at Mount Vernon (thanks to the Papers of George Washington and the really phenomenal Founders Online). It includes for the first time a précis and a link to Nancy Shoemaker’s review of Margaret Newall’s Brethren By Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery, because I wanted us to talk about the significance of Warren’s discussion of Native American enslavement in New England. And I was able to include one key document, a centerpiece of Warren’s final chapter, Samuel Sewall’s 1700 pamphlet “The Selling of Joseph,” because the Massachusetts Historical Society has wonderful online access to the full item (and in high resolution). I also added an example, also from the MHS, of a deposition concerning the contested claims to own two men in Boston in 1740, because I wanted to discuss the ways that slavery appeared in New England court records even if we couldn’t look at precisely the cases Warren was discussing.

The packets are certainly useful for me in that they help me to think through how the discussion might unfold. I think they have been variably successful in discussion because ideally I’d get them finished and sent out a full week before the group meets! But even if we don’t get to dig into them as much as I’d like each time, the fact of them reinforces the point about the necessary relationship of historical evidence (and the complexity of it) to argument.

The next book we’re reading (November 11) is Flora Fraser’s Princesses, the Six Daughters of George III. My plan is to create a packet well in advance that will facilitate discussion of the book, the sources that Fraser was able to use, because at the time she was one of the few scholars who gained access to the Royal Archives, and how the digitizing of the archive through the Georgian Papers Programme is changing what and how we can understand the wider world of the Georgians. I’ll be including in the source packet some of the materials from the GPP that are most important for Fraser’s analysis.

No Comments