July 4th is big. Never mind that independence was approved on the 2nd, and John Adams famously predicted we’d all be shouting huzzah and setting off fireworks 2 days ago. The 4th it is (the day that the Declaration of Independence was approved). And it’s a unique opportunity to reflect on what the United States was, is, and might be. Writing about July 4th is a distinct opportunity to assert and to wrestle with American ideas and practices. I’m fascinated by this phenomenon, as a historian but also also as a reader and writer.

Did I mention that in 2000 the Washington Post’s lead editorial for July 4th quoted me? I mention it embarrassingly often because it was such a riveting moment for me in every way, including opening the newspaper (yes, I still went to my front door to collect the paper) having no idea I’d been quoted and … then dropping it to call my parents, knowing that they’d have opened or be opening their morning papers, too.

It was also my first introduction to the power of online writing, as I’d written a piece to accompany the PBS series Liberty. I wrote about the experience of families falling on different sides of the conflict. The editorial, I think by then-editorial page editor Fred Hiatt, reflected on the American Revolution and quoted me for a lovely full paragraph and a half about specific family contexts, noting that “In the realm of politics and warfare, ardent Loyalists and avid Patriots traded sharp insults and ultimately mortal blows. In the realm of the family, such extremity could be tempered by sympathies engendered by close contact with and knowledge of “the enemy.” Though I’d quibble with this extension of my argument (and even with my own focus, which was on the Philadelphia Dickinson, Norris, and Thomsons), the editorial was making the point that American conflicts don’t have to be irrevocable. It concluded that “America did well to conclude what was, in many ways, a civil war without one side’s condemning the other to wholesale exile and destruction. Its future relies on a continued understanding, through the bitterest of national controversies, that “the enemy” whoever it might be, is still one of us.

I read all of this very differently in 2018 than I did on the excited morning of July 4, 2000.

More of that from me in another post, but for now, here’s a round-up of just some of the July 4th writing this year, which seems (anecdotal evidence only!) to be more intense and profuse than ever. I’ve only scratched the surface. (I wrote about July 4th writing last year, too.)

Museums and Archives

The National Archives has a nifty blog post about the Dunlap broadside: “The National Archives is famous for displaying the engrossed parchment copy of Declaration, but what’s lesser known is that we also have a Dunlap Broadside in our possession. It has been displayed only occasionally as a very special document display—only 26 known copies survive.” The post includes a short video explainer with curator Alice Kamps.

And of course the Archives also highlights the pages on its website that include images and explanation about the parchment copy.

The Library of Congress has on online exhibit about the Declaration, including their manuscript copies of the Declaration in Jefferson’s hand.

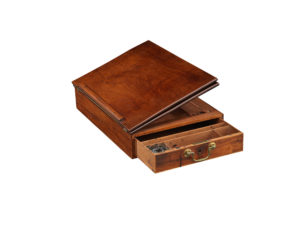

The Smithsonian National Museum of American History shared a blog post with some of its Independence day treasures, including Thomas Jefferson’s writing desk. Yes, that’s the very one on which he penned the document he wrote with the committee that included John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut.

Monticello’s recent opening of an exhibit on Sally Hemings garnered national coverage (see Annette Gordon-Reed’s important piece in the New York Times “Sally Hemings Takes Center Stage”; other NYT here, and WaPo coverage here, for example) and inspired some appropriately July 4th reflections from NYT writer Brent Staples, “The Legacy of Monticello’s Black First Family.”

Podcast

This week’s Ben Franklin’s World is a special episode, highlighting frenemies John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, and what they can teach us about patriotism and partisanship. That might sound glib, but I’m perfectly serious. Those two intellects and personalities have much to share about the period of the Revolution and the early United States, and there could be no better guide to the way histories of these two, and this essential era, have unfolded than Liz Covart in conversation with documentary editors extraordinaire Sara Georgini (The Adams Papers) and Barbara Oberg (the Papers of Thomas Jefferson). Plus, some cool appearances by folks voicing the principals. Come on, you can’t tell me you aren’t all recognizing these voices (especially Jefferson)??

Blogs

Edith Gelles wrote a great piece on the OI blog to accompany the BFW episode. “Abigail and Tom” shows us an important aspect of the Adams-Jefferson correspondence; as she writes, “Neither Abigail nor Jefferson minced words.”

No July 4th would be complete without substantial discussion of Frederick Douglass’s profound essay, “What, to the Slave, is the Fourth of July?” It is reproduced here on Black Perspectives. Democracy Now has audio of James Earl Jones reading it. This essay in The Atlantic, “When the Fourth of July was a Black Holiday” opens with it. Martha Jones posted on medium about William Watkins, writing about July 4th in 1831: “Before Frederick Douglass.”

Emily Sneff of the Declaration Resources project wrote a terrific piece for Age of Revolutions about the early history of publicizing the Declaration. In “Convulsions Within: When Printing the Declaration of Independence Turns Partisan,” Sneff notes that “The New York Times first devoted an entire page to the Declaration of Independence exactly 100 years ago, on July 4, 1918,” but that “the tradition of publishing the Declaration annually on July 4 dates much further back.” And it was rarely without debates over the meaning and implications of the document and the Revolution it marked.

Declaration Resources

We celebrate American independence today, but the relationship of national independence from Britain to the Declaration of Independence is a fascinating one, and often conflated. What exactly is being commemorated on July 4th? As an episode pointed up dramatically last year, when NPR tweeted lines of the Declaration at a time, horrified reactions suggested not only that lots of folks don’t know the document, but that they don’t necessarily understand the context or the intention behind it.

Because they have been doing yeowoman work to bring more information about the Declaration to light, earning plenty of new social media follows and references this year, It seems only fair that Declaration Resources gets its own section. This project, led by PI Danielle Allen of Harvard and with Emily Sneff, has been both prolific in its own right and inspiring others.

The work of the Declaration Resources team in identifying a copy of the Declaration in the UK as one of the very few parchment copies made the news again this week in various UK outlets including the Chichester Observer in West Sussex (a local paper).

Declaration Resources published a series of Fresh Takes on the Declaration of Independence for July 4, 2017. I got to participate with a great group of historians reflecting on what a new reading of the Declaration means. For me, it was about the past and our present. “Historians live in the now as well as the past; in the politics and the civic rituals of the present, the essence of American democracy can feel both precious and elusive.” And it was also about the holiday as a holiday, in which the text of the document plays a key role. When my children were small, I helped lead readings of the Declaration for neighborhood parties; as my children got older they did the reading. I have some pretty spectacular video of them reading in their homemade tricorn hats.

Joe Adelman was inspired in part by the invitation to Fresh Takes, but also by his annual teaching of the Declaration, to offer his own take for this July 4th. Joe reminds us of the position of the authors and signers, both looking back and looking forward: “We often think of the Declaration as forward-looking, presenting natural rights and offering a beacon for future generations. But reading it with the 1776 audience in mind underscores its focus on the past. Indeed the Declaration offers nothing for the future but the “Lives, [] Fortunes, and [] sacred Honor” of the delegates. The prospect of independence must have been exciting to many. But many hearing or reading the Declaration for the first time must have thought, “What’s next?”

Editorials

Because it’s July 4th, with its traditional reflection on American political values, and because Monday is the 150th anniversary of the 14th amendment, the New York Times uses the amendment as the focus of a piece about how, amid extraordinary strife, America can “start over” in ways more true to the nation’s ambitious language of democracy and equality. As part of its coverage for the holiday, the Times also asked an astonishingly homogenous group to opine on “What Does the United States Stand For?”

In The Washington Post, an editorial suggests that “America First,” a provocative phrase with darkly historical resonance, should instead recall to us “America as leader of a worldwide movement toward government of, by and for the people.” In the Post’s excellent Made by History series edited by Nicole Hemmer and Brian Rosenwald, historian Jeanne Abrams remembered the ladies, focuses on the women of the political elite, including Abigail Adams, and their role in the Revolution. John Garrison Marks with the American Association for State and Local History asks “Will America’s 250th birthday bring the country together or sow even more discord?” And he calls important attention to the need for historians to engage the upcoming anniversary in 2026.

I’ll bet all of you have wonderful local papers that are running July 4th editorials. In the Omohundro Institute’s local newspaper, the Virginia Gazette, a piece contrasts two men, one who works directing Dominion Power’s development into the James River and the other Bill Kelso, storied archaeologist of Jamestown, on opposite sides of the river and a key issue of historical and environmental concern. In another local paper in our region with roots in the early American past, the Annapolis Capital (which originated as the Maryland Gazette) ran a moving editorial about why its staff is marching in the July 4th parade. It’s both not as simple as it seems, and perfectly straightforward. After the terrible violence at the Capital Gazette, “we’ll be on West Street and Main Street because we want our readers and our community to see that we believe things will, eventually, be OK again. Eventually.”

Some of my Fav July 4th Twitter: