Here in Virginia it’s another important election day, and I’m about to host another reading group for life-long learners. This group of (mostly) retirees comes to the Omohundro Institute to discuss a mix of explicitly scholarly and dual-audience history. This year we began, by request from returning readers, with Kathleen Brown’s 1996 OI book, Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia. Many of the folks in the reading group also attend an OI life-long learner short course through William & Mary’s Christopher Wren Association. In the last two years those courses focused on various topics, including Digital Early America. In 2018 we’ll be teaching #VastEarlyAmerica. Packing about 35 people in our seminar room for several Wednesday mornings in the spring, we get a chance to talk about the history we know is important with a fresh audience. The hardcore group has been turning out for the extra, year-round reading group, and the discussions have been great. The schedule and previous reading list is on the OI website.

Many historians are increasingly attentive to, or at least very vocal about, the value of speaking, teaching, and writing about history as a form of civic engagement. The most obvious examples in the last months have centered on the fate of Confederate memorials, and the role they played in the twentieth-century politics, and are playing in the twenty-first century politics, of racial violence. There are so many ways in which historians can take civic action, one of which is addressing, as in that case, a specific history or historical developments.

By reading scholarly books with non-specialists, I get to share not only the history, but the scholarly process. We focus on that essential relationship of argument to evidence– and by extension, method. What constitutes evidence? How do we assess different types and uses of material? How tightly or creatively is an author using that evidence? In an age when discernment seems broadly fragile, when the difference between heated comments and bot-generated, targeted bile has become difficult to parse, when digitally altered text and images about, this small exercise in critical reading seems not only important, but a logical extension of my work.

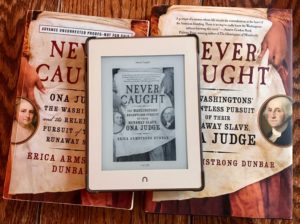

This week we are reading Erica Armstrong Dunbar’s 2017 book, Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge. I have this book in several formats, the hardcover I read most closely, the e-book I took with me when I was traveling last week and wanted to keep reading, and the signed proof copy that Erica gave me last year– that’s a treasure! This book, which I’ve regularly described as one of the most important founding era biographies and one of the most important books about George Washington, is a stunning look at how Ona Judge managed to escape and to make a new life for herself and her new family. But it’s also and fundamentally a book about the practice of racial slavery, as practiced by America’s first president.

And it’s a terrific use case of source material. What little there is to document Judge’s life before and after slavery is patiently detailed. The explicit depictions of slavery and Judge’s case in the Washington correspondence, cited in some other recent work, is unpacked and put into its most urgent context: Judge’s. I admire the book’s light touch, moving along at a good pace while taking time to illustrate how Judge experienced Mount Vernon, New York, Philadelphia, and then her life in New Hampshire. It makes this a perfect book for a source packet.

I’ve attached here the materials that I shared with the reading group and that we’ll be discussing alongside Never Caught today. These are all materials that are central to Erica Armstrong Dunbar’s narrative and argument. I included information about where to locate each source, and we’re going to discuss, too, how they can seek out these (and other) primary sources. I started with the Pennsylvania Act for the Gradual Emancipation of Slavery (1780) and ended with the text of Ona Judge’s 1845 interview in The Granite Freeman.

Most days we do what we can to make a difference where we think we can. On this election day it feels just right to be talking about how to discern the sources that reveal the story of a woman who fought for freedom over 220 years ago, and appreciating the woman who has brought her story to light.

1 Comment

Chefs’ Selections: The Best Books Read During 2017 Part 1 - The Scholarly Kitchen

at[…] enthusiastic about Never Caught, I assigned it to a local reading group for lifelong learners, and made a primary source packet to spur discussion of reading scholarship with a close eye on the relationship of argument to […]