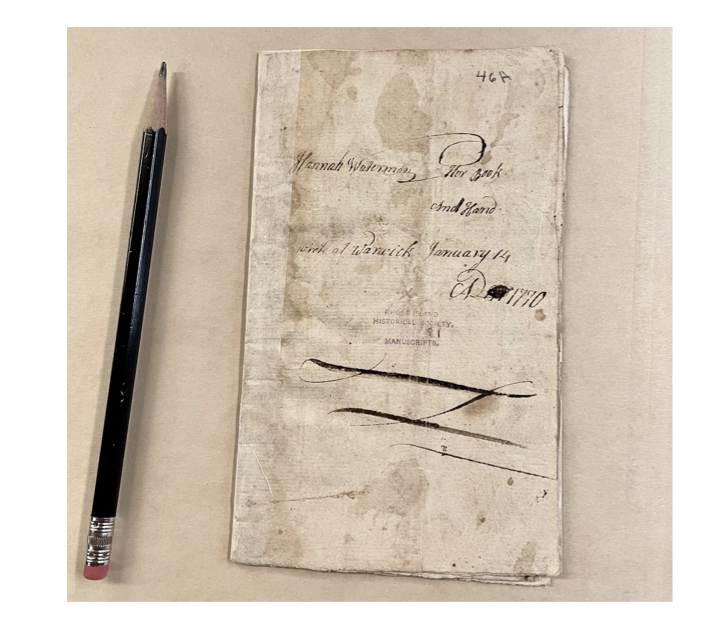

“Hannah Waterman Her Book and Hand wrote at Warwick January 14 AD 1770” is a family record book, just 16 pages, comprised of folded and single sheets stitched together with a few tantalizing suggestions of what might be missing. It is both like and unlike the many examples of such eighteenth-century genealogies I’ve seen in my research. Not many start with a woman’s hand and authorship, for example, though this one likely didn’t either. It clearly includes pages written by earlier generations –the first page by Hannah’s father–and as the work of multiple hands it is very like other family records.

Last month I participated in the marvelous Archival Kismet conference, an informal online conference developed by historian Courtney Thompson to, as she put it in a blog post on Nursing Clio, allow the archival materials you stumble across “to guide you, and [to be] open to questions and topics well outside of your wheelhouse.” She had in mind that historians would explore more and different literatures and fields, learning as we go, rather than focusing always on one place/ time/ topic.

I confess I subverted the remit a bit by talking about a family history record! But it’s one I only started to work with last Fall as I first began to explore in earnest the collections of the Rhode Island Historical Society. I’d worked in the RIHS collections some years ago, but only returned to deeper now that it’s just a few blocks from where I work. What extraordinary collections they hold and, as ever, family histories aren’t always where you’d expect them to be within it.

Two things I’ll point out about Hannah Waterman for now. First, the title page is itself both provocative and compelling. Bringing together not only the information but also the texts written by others and then titling the little book as hers makes this unusual. She would have been twenty when she wrote that it was “Her Book.”

And second, the size of this volume is perfect for a pocket– a woman’s pocket, that is. Plenty of good scholarship has explored how and where women wrote as well as what they wrote. Size of books made from folded papers is somewhat confined by the size of standard papers. But that size, shown here as relative to my pencil, was an intimate one. It was befitting of the intimacy of the material it contained. Losses– a brother who never returned from going to sea–”Remains on Heard of”–and parents dying old, children dying much too young.