Vast Early America is a phrase I coined in 2016 to use as a hashtag, but #VastEarlyAmerica isn’t of my making, of course. This way of understanding an expansive early America is the work of decades of scholarship. To my mind, it’s an urgently needed perspective on the foundational American history.

I spoke quite a bit about Vast Early America this year, in webinars, at conferences, in public forums. I also wrote a couple of pieces about Vast Early America, and wanted to gather and reference them in one place.

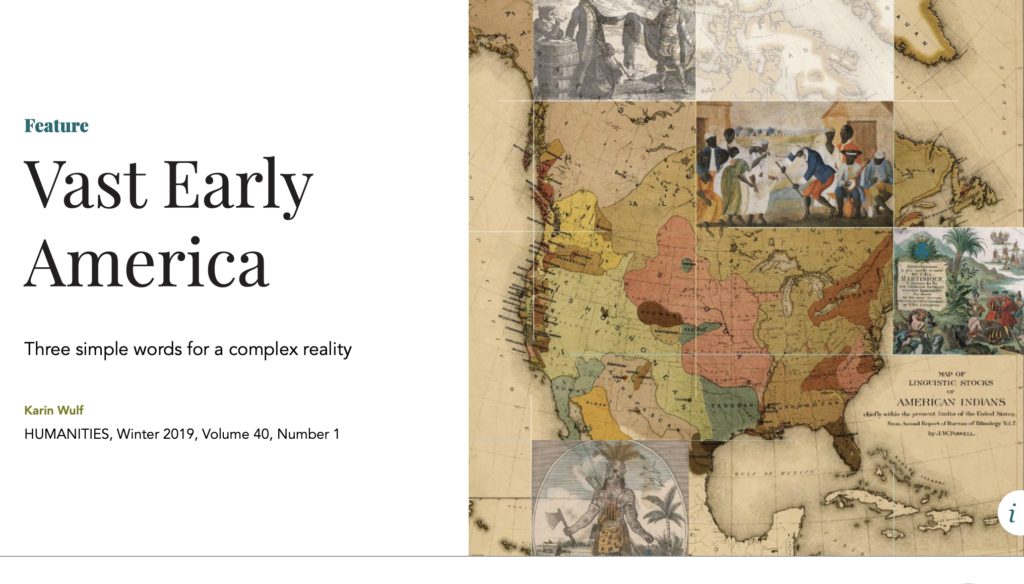

In January I published a piece, “Vast Early America,” for the National Endowment for the Humanities Magazine, Humanities.

American history courses usually begin with the peopling of the Americas, then move on to European colonization and the crisis of the British colonies. Tethered to the East Coast, historical attention turns west again as the United States expands its territorial claims in the nineteenth century. But a more expansive view of early America—what I and other scholars have taken to calling “vast early America”—would help us better understand the colonial and early national periods as well as the full sweep of American history….

Some recent critiques of early-American scholarship note that increased attention to diverse people (women, enslaved African Americans, Native Americans) and places (California, the Caribbean, West Africa, Atlantic port cities) takes us outside the framework that marches us from Colonial (British) America to the Revolution to the early United States. According to this complaint, the broader view of early America renders us less able to speak to the nature and origins of our nation. The argument for the traditional version of early America is that the basic laws and governance of the United States are rooted in an Anglo-American tradition, which is occluded by attention to the longer histories of places and people less closely connected to that tradition or that only “became” part of the American polity later on.

I could not disagree more. I would even go so far as to say that an American national history that does not see the depth and breadth of Native America across its historical landscape, that does not see slavery lying at the bedrock of the American experience, that overlooks the centuries-long significance of Mexican-American heritage cannot appreciate the great democratic ambitions the United States has articulated, defended, and pursued for almost two and a half centuries.

Go back to 1757. As the musical Hamilton asks, How did “a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman” from a “forgotten spot in the Caribbean, grow up to be a hero and a scholar?”

Hamilton’s story is an early American story about the economy of Caribbean sugar and slavery and about the nexus of indigenous, African, English, French, Spanish, and other people across the huge expanse of early America from which he emerged. Yes, he was well read in political philos-ophy, and he went on to wield his skills to remarkable effect. And a well-developed, and still growing, political history of Anglo America will always be an essential part of American history. But it is only a part.Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, and other political leaders of the early, eastern United States will continue to stride through the pages of our histories, but they will occupy that space as slaveholders as well as political leaders, and they will share that space with other people and places that will help us understand these founders better. A capacious approach to early America shows us a past that was infinitely complex, dynamic, globally connected, and violent. And it also still shows us—better shows us—the origins of an ambitious, powerful, and democratic nation. In short, we need an early American history, but one that fully grasps the depth, breadth, and complexity—the vastness—of early America. That is both good history and good civics.

“Vast Early America,” HumanitiesWinter 2019, Volume 40, Number 1

In March I had the fun and the great privilege of chairing a session on Vast Early America at the Organization of American Historians meeting, with a fantastic panel of Christian Crouch, Ronald Johnson, and Michael Witgen. The audience was large, and ready to talk. I wrote about the session for the Omohundro Institute’s blog, “Must Early American be Vast?” I’ve included in that post some links to other work referencing “Vast Early America.” And, continuing the theme of how and why Vast Early America is not only resonant but really vital, I wrote about the conversations at the session on national history.

If, as the participants on the roundtable and many in the audience seemed to feel, a vaster early America is incredibly important to American national history, how does that national purpose relate to scholarly and decidedly non-national ones? Or, as a member of the audience put it, if the French Atlantic is surely part of Vast Early America, is it necessarily of interest to Americans? And what if the answer is no? If aspects of this historical field are not purposed to the civic interests of contemporary Americans, are they any less important?

Of course not; quite the reverse. We begin our work as historians—as scholars, we study the past on its own terms. From that perspective it is quite clear that it isn’t the distortions of a twenty-first century lens that makes early America look vast. The kinds of work that have brought scholars to see an expansive geography and diverse people as part of a culturally, economically, intimately, politically, connected past has been driven by equally complex scholarly impetus.

Yet there is something inherent in this recognition of an early American past as complex and diverse that speaks to an urgent civic need. There is nothing simple about even the most traditionally confined early America; the narrative of a British colonial-into-Revolutionary America-cum-United States is itself an exceptionally complex and contingent history. Setting that history within a wider continental, Atlantic (and beyond)—yes, vast—context can let us better appreciate that complexity and contingency. And at the same time, perhaps more importantly, it illuminates a fuller and truer early America.

“Must Early America be Vast?” Common Sense Blog, May 2, 2019

Last year I wrote about teaching a graduate seminar on Vast Early America, and I’m scheduled to teach that seminar again in the coming year. That, and much more in the coming year, will surely provide more opportunities to speak and write about the what and why of Vast Early America. Stay tuned.

No Comments